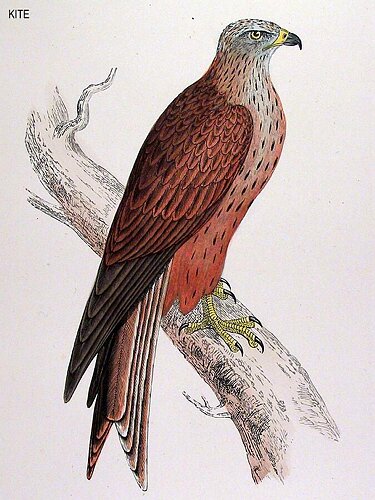

KITE.

BARCUD, IN ANCIENT BRITISH. GLEAD. PUTTOCK. FORK-TAILED KITE.

Milvus regalis, BRISSON. Falco milvus, LINNAEUS. Milvus Ictinus, SAVIGNY.

Milvus vulgaris, FLEMING.

Milvus—A Kite. Regalis—Royal—regal.

The Latin and English names of this species are to say

the least, inconsistent with each other, the word 'Kite' being equivalent

in our language to the word craven or coward, and the term 'Royal'

being inseparable from the idea of spirit and bravery. Nevertheless,

the ap pearance of this bird is certainly stately and handsome, and

if his inward qualities do not correspond with it, and with the name

he can only thence have derived, it is no fault of his, he is as nature

made him, and well it were if his highest superiors in the scale of

creation could all say as much. Buffon however asserts that the name

'Royal' has been given to it, not from any supposed royalty in itself,

but because in former times it was considered royal game.

The Kite is common throughout Europe, being found even in very northern

latitudes. It inhabits Italy, France, Switzerland, and Germany; is

not very uncommon in Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Russia, and is met with,

though rarely, in Holland. It is also found in various parts of the

north of Africa, and over Siberia and the greatest part of Asia. Clusius

relates that this bird was formerly very abundant in the streets of

London, and very tame; it being forbidden to kill it on account of

the use it was of, in acting the part of a scavenger.

The Kite is described by authors as being local in this country, and

strange indeed would it be if it were not. Where is a bird of its

size, and of its handsome appearance, and which is moreover so easily

caught in traps, and so destructive of game, to remain incognito,

or in safety in these days? The marvel is that a single specimen survives,

'sola superstes,' as a living monument of the former existence of

its kind. In these times of so-called 'progress' it is however to

be feared that even this state of things may not continue—no

'Aborigines Protection Society' exists for the Kite.

In Yorkshire, this bird has been in former times far from uncommon,

but the following are all that are now on record. About twenty-five

years ago one was caught in a trap at Edlington wood, near Doncaster,

and a pair were taken from the nest by Mr. Hugh Reid, of that place.

One was obtained in Hornsea wood, in 1833, and another in Lunn wood,

both near Barnsley, in 1844. It has been observed, but very rarely,

near Halifax, and one was seen by Charles Waterton, Esq., near Huddersfield.

Others by Sir William Jardine, Bart., and one by Mr. W. Eddison, shot

near Penistone, but there is no notice that I am aware of, of any

having been met with in the North or East Ridings. Not far from Alconbury

hill, a well-known place on the old 'Great North' road, (how different

in all but name from the 'Great Northern,')—a locality in which

I perceive that Mr. Hewitson records that he has seen it, I had the

pleasure some years ago of seeing the Kite on the wing; too striking

a bird, when once seen, not to be easily recalled at bidding before

the mind's eye.

In addition to the before-named places, this 'Royal' bird has been

a dweller in several parts of Wales, and of Scotland. Many have hitherto

found a temporary refuge in various parts of the 'far north.' The

waters of Loch Awe have reflected the graceful flight of some, and

the 'bur nished gold' of Loch Katrine has been darkened by the passing

eclipse of others. In Sussex it was, says Mr. Knox, indigenous in

former times, but is now no longer known there, only one near Brighton,

and one near Siddlesham, having occurred within the last ten years.

In the New Forest in Hampshire it has hitherto been frequently seen.

In the parish of Hursley, near Winchester, it is recorded by W. P.

Heathcote, Esq., to have been formerly very common, and occasionally

to have bred there. It used also to be seen constantly about the meads,

but this is many years agone. In Devonshire it seems to be very rare:

Montagu only observed one there in the course of twelve years; Dr.

Moore has recorded a few; one was caught on Trowlsworthy warren, Dartmoor;

one at Widey, in 1831; one at Saltram; and one at Sydenham, in 1835.

One at Countessbury, near Lynmouth, in April, 1861, and one near Austen

Gifford, in October, 1862. Another at Croome Court, Worcestershire,

the seat of Lord Coventry, in January, 1870. A few in Durham, Cumberland,

where the woods around Armathwaite and Ullswater are or were breeding

places; Northum berland, Westmoreland, Essex, and Hertfordshire; very

rarely in Gloucestershire—between Gloucester and Bristol, according

to Mr. Knapp. In Norfolk one an old male was caught in a trap near

Thetford, November 16th., 1888. In Lincolnshire it used to be not

uncommon in the neighbourhood of Swinhope, as the Rev. R. P. Alington

informs me; also at Bradfield, in Berkshire. One was killed at New

Romney, in Kent, in 1840; one at Lincoln, October 25th., 1851, as'Mr.

William Felkin, Junior, has informed me. One caught in Blenheim Park,

Oxfordshire, of which James Dalton, Esq., of Worcester College, Oxford,

has written me word. In Cornwall at Trescobeas, Tolvern, Swanpool

1846, and Pennance 1846. I was very glad to hear of one seen by Colonel

Prescott Decies, of Bockleton Court, near Tenbury, Worces-tershire,

May 9th., 1881, of which his daughter Miss Ruth Prescott Decies wrote

me word. Also Mrs. Georgina Pasley, of Moverhill, Botley, Hampshire,

of a pair there for several years.

It is said by J. J. Briggs, Esq., in his catalogue of the Birds of

Melbourne, (the Derbyshire place of that name,) to be there some-times

seen sailing over the grass fields at a considerable height, in a

steady and graceful manner; and the Rev. Messrs. Matthews, in their

catalogue of the Birds of Oxfordshire, say likewise, that a few years

ago it was so common there, that occasionally two or more might be

seen at the same time about its favourite haunts, but that it has

now become very scarce.

In the Hebrides it appears to be unknown. In Sutherlandshire it is

becoming very rare, though formerly common. On the banks of Loch Fine

it is said by Sir William Jardine to be more abundant than in any

other quarter of the country, on Ben Lomond, as also in many parts

of the western Highlands, Aberdeenshire, Stirlingshire, Nairneshire,

and Argyleshire, but only north of the Forth, being almost entirely

unknown in the south of Scotland; Gledsmuir (?) Mr. Macgillivray says

that in the space of eight years only one specimen came into the hands

of the Edinburgh bird-stuffers. In Moray, the Rev. G. Gordon says

that it is sparingly diffused in the more wooded districts, that a

pair built in 1832, near Cowder Castle, one of which was killed. Thomas

Edmonston, Esq., Junior, says, that it is an occasional straggler

in Shetland. One was killed by the gamekeeper of G. S. Foljambe, Esq.,

in the year 1838, on a hill near Rothes.

In Ireland, it is stated by Smith, in his history of Cork, which was

completed in the year 1749, to have been at that time common. Now,

however, it is said by William Thompson, Esq., of Belfast to be known

only as a very rare visitant. The Rev. Joseph Stopford has seen it

at Ballincollig Castle, in 1827, and near Blarney. In the Park of

Shanes Castle, the seat of Lord O'Neil, two were seen by Mr. Adams,

his lordship's gamekeeper, one about the year 1830, and the other

in March, 1835. Others are said to have been observed in the same

park in previous years, and one was once seen by William Ogilby, Esq.,

in the county of Londonderry.

It retires in great numbers from the north of Europe to Egypt and

the northern shores of Africa before winter, staying there to breed,

and re-turning again in April to Europe, where it breeds a second

time, contrary to the nature of rapacious birds in general. It remains

with us the whole year, but may be, and indeed probably is, partially

migratory.

In proof of the docility of this species, it may be mentioned that

R. Langtry, Esq., of Fortwilliam, near Belfast, had a pair brought

up from the nest, which were given their liberty every morning, and

after soaring to a great height in the air, used to return and come

to call.

The flight of the Kite is rapid, and like several other birds of prey,

it soars at times to a vast height, and there frequently remains for

hours together, seemingly in the tranquil enjoyment of its easy exercise:

some-times it ascends beyond the reach of human vision, doubtless,

however, its sight far excelling ours, it can perceive objects in

the 'vast profound,' and at times it descends from a great altitude

upon its prey, with aston-ishing swiftness. One of the vernacular

names of this bird, the Glead or Gled, is derived, according to Pennant,

from the Saxon word 'glida,' descriptive of its gliding motion. Wheeling

round and round, supported on its extensive wings, and guided by the

steering of its wide tail, it thus by degrees advances, sometimes

for a time poising itself in a station-ary position. If its nest is

attacked or approached, it dashes in a wild manner around and near

its enemy, supposed or real, with screams, either caused by alarm

for its young, or intended to excite fear in its assailant. When searching

for prey, it flies at a moderate height from the ground at an elevation

of from about twenty to about one hundred feet, performing a variety

of sweeps and curves, and appearing, as indeed at other times, to

be not only guided, but almost partially supported, by its wide-spread

and expansive tail, which it moves about from side to side. Buffon,

quoted by Macgillivray, says of its flight,' 'one cannot but admire

the manner in which it is performed; his long and narrow wings seem

immoveable; it is his tail that seems to direct all his evolutions,

and he moves it continually; he rises without effort, comes down as

if he was sliding along an inclined plane: he seems rather to swim

than to fly.' Frequently, however, his flight is unsteady and dashing,

strongly resembling that of several of the Sea-gulls.

The food of this species consists of small quadrupeds, such as leverets,

moles, mice, rats, and rabbits; game, and other birds, especially

the young; as well as frogs, lizards, snakes, worms, insects, and

occasionally carrion, and it is said by Bewick that it is particularly

fond of chickens, but that the fury of the mother is generally sufficient

to scare it away.

In search of these, it, like the Sparrow Hawk, sometimes approaches

the poultry yard, but doubtless such approaches were far more common

in former times than now. Montagu, however, in his 'Ornithological

Dictionary,' gives an account of one which was so eager in its attempt

to obtain some chickens from a coop, that it was knocked down by a

servant girl with a broom, and he relates that on another occasion,

one of these birds carried off a portion of some food which a poor

woman was washing in a stream, notwithstanding her efforts to repel

him. They have been known to feed on fish, the produce of their own

capture from a broad river, and will readily devour the reliques of

a herring or other fishery.

The Kite, like the Buzzards, and unlike the Eagles and Falcons, does

not pursue its prey, but pounces down unawares upon it.

Its note is called by gamekeepers and others its 'whew,' a peculiarly

shrill squeal.

The author of the 'Journal of a Naturalist,' has the following curious

account in his entertaining and profitable book. He says, 'I can confusedly

remember a very extraordinary capture of these birds when I was a

boy. Roosting one winter evening on some very lofty elms, a fog came

on during the night, which froze early in the morning, and fastened

the feet of the poor Kites so firmly to the boughs, that some adventurous

youths brought down, I think, fifteen of them so secured! Singular

as the capture was, the assemblage of so large a number was not less

so; it being in general a solitary bird, or associating only in pairs.'

The truth of this fact has been doubted by some naturalists, but the

late Bishop of Norwich, Dr. Stanley, has brought together abundant

corroborative instances of a similar kind, which I intend to quote

when treating of the birds to which, they refer.

In the breeding season it is a common thing to witness conflicts between

the male birds. Montagu speaks of two which were 'so iutent on combat

that they both fell to the ground, holding firmly by each others'

talons, and actually suffered themselves to be killed by a woodman

who was close by, and who demolished them both with his bill-hook.'

It also at such times approaches the villages, which at other times

it avoids, perhaps searching for material for its nest. The young

are defended with some vigour against assailants. The hen sits for

about three weeks, and during that time is diligently attended to

by the male bird.

The nest is built early in the spring, between the branches of a tall

tree, but rather in the middle than at the top, and occasionally on

the ground in rocky places, and is composed of sticks, lined with

any soft materials; such as straw, hair, grass, wool, or feathers.

It is flat in shape, and rather more closely compacted than that of

some other birds of the Hawk family, and is generally built in the

covert of a thick wood.

The eggs of the Kite, which are rather large and round, very much

resemble those of the Common Buzzard, and possibly this fact may afford

some confirmatory justification of the juxtaposition of these birds.

The ground colour is a dingy white, bluish or greenish white, or dull

brownish yellow, and in some instances unspotted at all; in others

it is dotted minutely over with yellow or brown, or waved with linear

marks; and in others is blotted here and there with brown or reddish

brown, but especially at the lower end. They are generally two or

three in number—rarely four.

This handsome and fine-looking bird weighs light in proportion to

its apparent size, so that it is very bouyant in the air: its weight

is only about two pounds six ounces, or from that to two pounds and

three quarters; length, two feet two inches, to two feet and a half;

bill, yellowish, or yellowish brown at the base and edges, and dusky

or horn-colour at the tip. In extreme age it all becomes of a yellowish

colour; cere, yellow; iris, yellow; bristles are found at and about

the base of the bill. The head, dull greyish white, light yellowish

brown, hoary, or ashy grey, with brown or dusky streaks in the middle

of each feather along the shaft; the feathers are long, narrow, and

pointed. In some specimens the head is rufous. The feathers of the

neck are also long and pointed, which gives a kind of grizzled appearance

to that part; it is light yellowish red in front, each feather being

streaked with dark brown, and the tip reddish white; nape, chin, and

throat, greyish white; breast, pale, rufous brown, each feather with

a longitudinal streak of dark brown; back, reddish orange, or rufous

brown, with dusky or dark brown stripes in the centre of the feathers,

the margin of each being pale, or dusky, edged with rust-colour; the

breast is lighter than the back, and specimens vary much in depth

of colour in both parts.

The wings extend to five feet, and, when closed, two inches beyond

the tail; the quill feathers are dusky black, from the fifth to the

tenth dashed with ash-colour, with a few dusky bars, and white at

the base and on the inner webs; the rest are dusky with obscure bars;

of the tertiaries some are edged with white the under surface of the

wings, near the body, is rufous brown with dark brown feathers, edged

with reddish brown towards the outer part of the wing. The feathers

of the greater wing coverts are dusky, edged with rust-colour; the

two outer primaries, nearly black; the others greyish brown on the

outer web, and paler, barred with blackish brown, on the inner: the

fourth quill is the longest, the third only a little shorter, the

fifth neatly as long, the second a good deal shorter, and the first

much shorter than the second; secondaries, greyish black, or deep

brown, shaded with purple, the tips, reddish white, the inner webs

more or less mottled. The tail is the distinguishing feature in this

bird, as the legs are in the Rough-legged Buzzard: it is both wide

and long, and in general, though not always, even in very old specimens,

perhaps owing to the moult, very much forked. The bird may by it be

'challenged' at any distance from which it is brought in sight. Its

upper side is reddish orange, or bright rust-colour with white tips,

the outer webs being of one uniform colour, but the inner barred with

dark brown, the outer feather on each side the darkest in colour,

beneath it is reddish white, or greyish white, with seven or eight

obscure brown bars. The middle feathers are a foot long, the outer

ones between fourteen and fifteen inches. The two outermost, which

turn slightly outwards at the tip, are dusky on the outer webs, the

first barred on the inner web with the same. The bars of the upper

surface shew through to the under: upper tail coverts, rufous, or

reddish orange; under tail coverts the same; legs, yellow or orange,

short, scaled, and feathered about an inch below the knee. The toes

are small in proportion to the size of the bird: the outer and middle

ones are united by a membrane; claws, black, or bluish black, and

not much hooked.

The female is, as I have so often had occasion to remark before of

the Hawks, considerably larger than the male. Length, two feet four

inches. Her plumage inclines more to grey and orange than his, and

the larger of the measurements given above belong to her. The feathers

on her head become gradually more grey, until they fade to a pale

hoary white. The wings extend to the width of five feet and a half.

The young, when first fully fledged, are of a deep red, especially

on the back, and the central markings of the feathers are darker and

larger than in the adult bird; the head and neck are also darker.

The iris is yellowish brown; the feathers on the back have a tinge

of purple; the bars on the tail are more distinct, and the colour

of it is darker than in the old bird.

In the young bird of the year the feathers of the head and neck are

shorter and less pointed, reddish in colour, and tipped with white,

the back more rufous than in the adult.

After the first moult, the young birds nearly acquire their perfect

plumage. The central dark markings on the feathers become less, and

their red edges paler with advancing age.

The varieties of this species as to size and colour, though not unfrequent,

are unimportant.

"The wheeling Kite's wild solitary cry."

KERLE