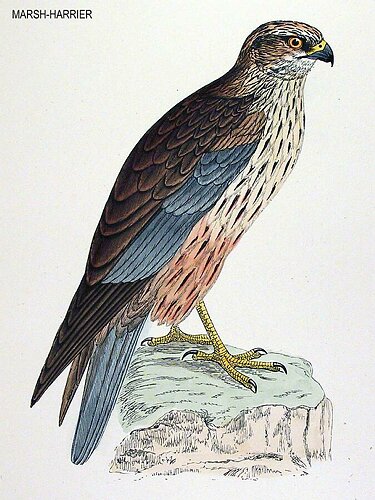

MARSH HARRIER.

BOD Y GWERNI, IN ANCIENT BRITISH.

MOOR HARRIER. MOOR BUZZARD. HARPY. HARPY HAWK. WHITE-HEADED HARPY.

PUTTOCK. DUCK HAWK.

Circus rufus, BRISSON. SELBY. Falco aeruginosus, Linnaeus. PENNANT.

Falco arundinaceus, BECHSTEIN.

Circus—The Greek name of some species of Hawk. Rufus—Red.

Why the birds of the genus at which we have now arrived

should be called Harriers more than any others of the Hawk family,

I know not. Yarrell suggests that the origin of the name has probably

been derived from their beating the ground somewhat in the manner

of a dog hunting for game, but not more so, I think, than some other

Hawks. Their natural order is certainly in close proximity to the

Owls; the most remarkable 'feature' of similarity being the ruff-like

circle of feathers round the face, somewhat after the fashion of what

in the human subject is called a calf-lick, and which is set up or

depressed by the voluntary action of the bird.

These Harriers are found in the temperate regions of three, if not

the four quarters of the globe. They are common in Norway and Sweden,

Aland, Denmark, and the south of Russia, Germany, France, Italy, Spain,

where it is very abundant on the banks of the Guadalquiver, Holland,

Belgium, and Turkey; less frequently in Switzerland, and the south

of Europe; in Egypt, Morocco, Tangier, Algeria, Abyssinia, and other

parts of Africa, as also in Teneriffe and the Canary Islands; the

Himalaya Mountains, Asia Minor, Siberia, Japan, India, Palestine,

and other districts of Asia. Wilson and Buonaparte consider this species

to be the same as the American one they describe by the name of the

Marsh Hawk, but several distinctive marks, as for example the difference

in the length of the tail beyond the wings, will appear on reading

their account, though they are right in overruling the erroneous reason

given by Pennant, namely, the thickness of the legs, for supposing

the birds distinct; whether therefore our species is found in America

I am not able to say.

In this country they are indigenous, remaining with us all the year

round in most of the counties of England and Wales; in Ireland, from

Antrim and Longford to Cork; and in Scotland, as in Aberdeenshire,

Perthshire, Banffshire, Argyleshire, and so on; also in the Hebrides

and Orkney. Their numbers, however, like those of so many others of

the birds of prey, are becoming gradually fewer, and anything but

'beautifully less.' From Scotland to Sussex an ornithological lament

over the glories of the departed is raised: 'Fuimus' must soon be

the motto of the Marsh Harrier, as well as of 'the Bruce.' It still

only survives in a few places—Nether Lochbar, Appin, and others.

In Yorkshire it sometimes visits the moors near Sheffield, and has

been not uncommon near Doncaster. Seven or eight were obtained one

season from Hatfield Moor and Carr Side: has occurred, rarely, at

Hebden Bridge. Many were procured in Devonshire in one hard winter,

In Cornwall—few, as one at Swanpool about the year 1853. Still,

too, a few in Norfolk, two in 1876, at Ormesby St. Margaret, as Mr.

J, Alfred Lockwood has informed me; Hampshire, Somersetshire, Shropshire,

and Dorsetshire. In Lincolnshire at Tetney. In Wiltshire one at Newfoundland

near Netheravon, the beginning of September, 1869; one also on October

5th.

They frequent, as the name suggests, open moors and wild plains, in

which marshes or lakes are found, but appear to be partially migratory.

Attempts have been made to train them for falconry, but they have

been found very intractable. It would appear, however, that they may

be kept in confinement, and become in a certain measure tamed.

The flight of these birds, which is not very swift, and mostly low,

is light, smooth and airy, but unsteady. Occasionally they rise to

so great a height as to be all but invisible to the eye, and at the

time when the female is sitting, the male is often to be seen soaring

above the nest, and performing a variety of attractive evolutions.

They seldom alight on trees, even to roost at night, but resort to

the concealment of beds of reeds, and in the day-time perch on a hillock,

a rail, a stone, low bush, or the ground. They do not long remain

stationary, but keep beating their hunting grounds in search of prey,

and they often frequent the same locality for several days together

and follow the like course at the same hour of the day.

The food of the Marsh Harrier consists of rabbits, water-rats, mice,

and other small animals, whether found dead or alive, land and water

reptiles, the young of geese, ducks, and other water-fowl, and of

partridges, as also small birds, such as quails and larks, the eggs

of birds, insects, and, Bewick and others say, fish, and Mudie, large

carrion. They take their prey from the ground or the water, not in

the air. In the autumn they sometimes leave the moors and come down

to the coast in quest of sea-birds, perching on the rocks until they

perceive any that they can seize. A singular anecdote of one of this

species, communicated by Mr. R. Ball, is recorded in Mr. Thompson's

'Natural History of Ireland.'—'One of these birds, which I had

some years since, lost a leg by accident. I supplied it with a wooden

one, and the dexterity it acquired with this stump, both in walking

and killing rats, was astonishing. When a rat was turned out, the

bird pounced at it, and never failed to pin the animal's head to the

ground with the stump, while a few grasps of the sound limb soon terminated

the struggle.' This reminds one of the gallant Witherington immortalized

in 'Chevy Chase,' of whom we read that 'when his legs were shot away,

he fought upon his stumps.'

Towards the end of the month of March, nidification commences, and

incubation in April; the young are hatched in May. The nest is usually

built among the high reeds which fringe the margin of the lake, pond,

or swamp; in a tuft of rushes, fern, or furze; occasionally on a mound;

at the edge of a bush, on the top of the stump or in the hollow of

the branches of some tree in any of the former situations. It is a

very rude fabrication, and is composed of sticks, with reeds, flags,

sedge, rushes, grass, or leaves, sometimes forming a mass a foot and

a half above the ground.

The eggs are from three to five in number, slightly tapered at one

end, and generally perfectly white, or white with a slight tinge of

blue. Bewick says that they are irregularly spotted with dusky brown;

and Macgillivray describes some he had seen which had a few faint

light brown or reddish brown marks.

This species varies exceedingly in plumage. Male; weight, about twenty-one

ounces; length, one foot seven to one foot nine inches; bill, bluish

or brownish black; cere, greenish yellow; iris, orange yellow; head,

but sometimes only the crown, yellowish or white; in some specimens

the shafts are dark; in others, it, as well as the whole of the plumage

is ferruginous brown; in others, it is yellowish white tinged with

rufous, and streaked with dark brown; and in others, only a shade

lighter than the rest of the brown plumage. The upper part of the

neck is encircled by an indistinct ruff of stiff feathers; on the

back and the nape, yellowish white, or white; chin and throat, nearly

white. Breast, ferruginous brown, streaked with a darker shade; the

shoulders are sometimes white. Back, ferruginous brown, the feathers

more or less margined with a lighter shade.

The wings, when closed, reach nearly to the end of the tail, and are

much rounded; their expanse four feet two inches; greater wing coverts,

ferruginous brown, but in older birds partially or entirely ash grey,

and in some tipped with reddish brown; sometimes yellow; lesser wing

coverts, the same. Primaries, brownish black, or dark grey in old

birds, slightly margined with brownish grey; the fourth feather is

the longest, the third nearly equal to it, the second a little shorter,

the first and sixth about equal. Secondaries, ash grey, tipped in

some cases with reddish brown; and also slightly margined with brownish

grey; tertiaries, ferruginous brown, margined with a lighter shade;

in older birds, partially or entirely ash grey. Larger and lesser

under wing coverts, light brown, the latter paler, and their extremities

brownish white; tail, long and slightly rounded, light brown or ash

grey, the side feathers irregularly marked on their inner webs with

brownish red, their tips brownish white, in some instances tipped

with reddish brown, the base tinged with yellow; tail coverts, ferruginous

brown; under tail coverts, the same, each feather streaked with dark

brown.

Legs, slender, long and yellow, feathered to within three inches of

the foot, in front they have a series of eighteen scutellae, behind

about ten, and the sides and behind the upper and lower parts are

reticulated; toes, long and yellow; claws, brownish black and slender,

sharp, and not much hooked; the outer and middle ones are united by

a membrane, and the latter is somewhat dilated on the inner edge.

On the first toe are five scutellae, on the second four, on the third

fifteen, and on the fourth ten.

The female resembles the male in colour, but is considerably larger;

weight, twenty-eight ounces and a half; length, from one foot ten

inches to two feet; bill, dusky or bluish black, its base tinged with

yellow; cere, yellow; iris, reddish yellow, Selby says dark brown,

but this must be a young bird; below it is a narrow space of brown;

ear coverts, brown. Head, yellowish, sometimes streaked with brown.

The neck is surrounded in front by a ruff of stiff feathers; on the

back yellowish white streaked with brown; nape, throat, neck in front

and breast, reddish brown, many of the feathers yellowish white, a

central spot along the shafts of brown; back, dark brown on the upper

part, with some yellowish white markings, on the lower part the feathers

tipped with brownish red. The wings expand to the width of four feet

five or six inches; the lesser wing coverts have a large patch of

yellowish white. Primaries, blackish brown, glossed with purple, their

inner webs paler at the base, and slightly dotted with brown; secondaries,

paler brown, each slightly margined with pale brownish grey; tail,

light brown, tinged with grey, the side feathers variegated with brownish

red on the inner webs, and all tipped with reddish white. Legs and

toes, yellow; claws, brownish black.

The young, when fully fledged, are entirely of a chocolate brown colour;

the cere, greenish yellow; the bill, yellow at the base, and brownish

black towards the tip; the iris, deep brown; the feathers of the upper

parts slightly tipped with reddish brown; the greater wing coverts

largely tipped with pale brown; the upper tail coverts bright reddish

brown.

The young in the first year, formerly described as a separate species

by the name of the Moor Buzzard, have the bill bluish black; cere,

pale yellowish green; iris, dark brown; crown and back of the head,

dark cream-colour, or light brownish red; sometimes a portion only

of the head is of this colour—the top, the sides, or the back.

Neck, nape, and chin, brown; throat, yellowish white or light rust-colour;

breast and back, dark reddish brown with a metallic tint; the latter

becomes paler as the bird advances in age. Greater wing coverts, sometimes

tipped with white; lesser wing coverts, tipped with light red; primaries,

secondaries, and tertiaries, reddish brown. Larger and lesser under

wing coverts, brown, gradually of a lighter shade. Tail, tipped with

light red, the brown becomes gradually paler, its inner webs lighter,

and variegated or mottled. The male bird has six or seven bands of

red, which subsequently turn to grey. Tail underneath, pale ash grey;

it becomes paler by degrees; tail coverts, reddish brown. Legs, long,

and toes, pale yellowish green; claws, black. In their second summer,

the plumage becomes more rufous in some parts, the tail lighter coloured,

and on the ruff and the shoulders, and front of the neck, some yellowish

white spots shew themselves, and an ash-grey gradually spreads itself

on the greater wing coverts. In the third year, the back is light

rufous brown; the tail, pale grey, without any bars, and its under

surface, as are the wings underneath the quill feathers, of a silvery

white.

'Individuals differ considerably in colour, but chiefly in the extent

of the yellowish white of the head and neck. Sometimes the crown of

the head and the throat only are of this colour, with indications

of the same on the hind neck and shoulders.'

Latham describes a specimen of this bird as of a uniform brown, with

a tinge of rust-colour; Montagu one which had the head, some of the

wing coverts, and the four first quill feathers, white; Selby one

which had the four quill feathers, throat, part of the wing, and the

outer tail feathers, white; and the Eev. Leonard Jenyns one in which

the lower half of the breast was white, and others spotted with white

in various parts. Some have the upper part of the breast, and others

part of the back of the neck white; others, without the white head,

have a greyish spot on the throat. Sir William Jardine describes one

as entirely brown, excepting the forehead and back of the head, throat,

sides of the mouth, and tips of the quills, which were white; another,

pale reddish brown, the upper tail coverts and base of the outer tail

feathers pale yellowish red, the former shewing a bar; the back of

the head pure white, extending over each eye.

I have much gratification in communicating the following new theory

of what will, I have hardly a doubt, prove to be the fact of the case

respecting the striking changes in the plumage of this bird. Mr. Arthur

Strickland has written down for me the substance of a previous conversation

on the subject, as follows:—'This bird has a regular periodical

change of plumage that has not, as far as I know, been before explained.

It begins life in a dark plain brown plumage, with a distinctly defined

dark cream-coloured head; it then leaves this country as it is a regular

migratory species; it returns the next spring in a much lighter brindled

brown plumage, with a pale orange-coloured head, which pale orange

in old specimens extends over part of the neck and shoulders; but

in the intermediate time it has undergone a marked change of plumage,

losing entirely all portions of the cream-colour of the head, which

is in fact only a breeding state of dress. In the winter dress it

is of very rare occurrence in this country, but if by chance it does

occur, it will be found as above described, in all respects answering

the description of the Harpy Hawk of Brisson; but specimens taken

upon their first arrival in spring, may be often got with the cream-coloured

head only partly developed.' A variety of this bird was deep brown,

almost black, all over.

It is a very curious fact that Mr. Arthur Strickland has met with

no young birds from the nests in Yorkshire without the white cap on

the head, and the Rev. Leonard Jenyns none in Cambridgeshire that

had it; and further, in a communication to Mr. Allis, Mr. Strickland

says that the only adult bird without the white cap he ever saw, was

from Cambridgeshire, which is certainly very singular. Can there be

two species confounded together?

In old individuals the festoon of the bill is more distinct, and the

bill itself larger; the toes and claws stronger.

"Some haggard Hawk which had her eyrie nigh

Well pounced to fasten, and well winged to fly."

DRYDEN.