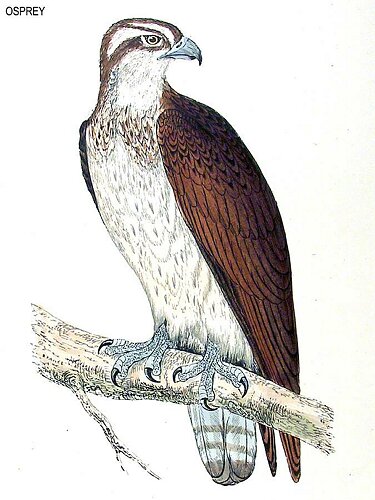

OSPREY.

FISHING HAWK. FISHING EAGLE. BALD BUZZARD. FISHING BUZZARD. PYSG ERYR,

GWALCH Y WEILGI, IN ANCIENT BRITISH.

Pandion haliaetus, SAVIGNY. VIGORS. SELBY. GOULD. Falco haliaetus,

BEWICK. PENNANT. MONTAGU. LATHAM. LINNAEUS. Balbusardus haliaetus,

FLEMING. Aquila haliaetus, JENYNS. MEYER.

Pandion—The name of a Greek hero, changed into a bird of prey.

Haliaetus. (H)als—The sea. Aietos—An Eagle.

It is not every one who has had the fortune-the good

fortune-to visit those scenes, where, in this country at least, the

Osprey is almost exclusively to be met with. In these, which may in

truth be called the times of perpetual motion, there is indeed hardly

a nook, or mountain pass, which is not yearly visited by some one

or more travellers. Where shall the most secure dweller among the

rocks be now free from the intrusion of, in ornithological language,

at least 'occasional visitants?' Still the case is not exactly one

to which applies the logical term of 'universal affirmative.' Though

every spot may be visited, it is not every one who visits it. How

many of those who shall read the following description of the Osprey,

have taken the "grand tour'' of Sutherlandshire?

In that desolate and romantic region, though even there at wide intervals,

and 'far between.' and in a very few other localities, the Fishing

Hawk may yet be seen in all the wild freedom of his nature. There

it breeds, in the fancied continuance of that safety which has for

so many ages been real. You may see, even in the year eighteen hundred

and fifty, an occasional eyrie on the top of some rocky islet in the

middle of the mountain lake.

This species is very widely distributed over a large portion of the

globe, being met with, in greater or less abundance, in Europe, Africa,

and America, sometimes in very considerable numbers, and doubtless

in Asia also. In America it seems to be most particularly numerous,

a whole colony tenanting the same building place. It is also met with

in Russia, Siberia, Kamtschatka, Scandinavia, France,Spain, and Germany,

Switzerland, and Holland; in Egypt, Tripoli, Nigritia, the Cape of

Good Hope, Japan, and New Holland, and has been hitherto far from

unfrequent in England, most numerous at either extremity of the country,

namely in Devonshire and Sutherlandshire, and various other counties

of that part of the empire. One on the 11th. of March, 1864, in a

cover belonging to the Earl of Dudley, at Crogen, in the Berwyr Mountains.

Specimens have been killed in Berkshire, at Donnington, and at Pangbourne,

the latter one in the year 1810, in the month of January. One in Kent,

near Holling-bourne, in 1845; three in Oxfordshire, one of them at

Nuneham Park, the seat of George Harcourt, Esq.; and one at Udimore,

in Sussex, by the keeper of P. Langford, Esq., in November, 1848.

Others in Shropshire, Somersetshire, two so late as at the end of

the year 1878, at Brinscombe Court, near Stroud, of which Mr. E. G.

Edwards has written to me, and Hertfordshire. One, a female, shot

by Baron de Rothschild's keeper, at Weston Turville, Buckinghamshire,

the 10th. of October, 1853: one is mentioned by the Rev. Gilbert White,

in his 'Natural History of Selborne,' as having been killed on Prinsham

Pond, in Hampshire. In Herefordshire near Ross, in October, 1879,

and one on the estate of Lord Kingston in May, 1885. Another in Christchurch

Bay, where, Mr. Yarrell says, this bird is called the Mullet Hawk,

a name far from unlikely to be appropriate, for these fish are remarkably

fond of basking near the surface of the water, so that they may easily

be killed with stones as I have known before now. A specimen was shot

in the year 1824, at Alverbank, and another, which appeared to be

its mate, frequented the Solent for the two succeeding summers. One

at Wentworth Castle, etc.

In Wales one at Gloddaeth in 1837.

It has been in the habit of building regularly in many parts of Scotland,

on Loch Awe, Loch Lomond, Loch Assynt, Scowrie, Loch Maddie, near

Durness, and Rhiconnich, in Sutherlandshire, Tantallon Rock in 1867,

Glendha, Loch Inchard, Loch Dolay, Loch Menteith, in Caithnesshire,

Rosshire, in short, on many or most of the Highland Lochs, also Killchurn

Castle, on the Pentland hills, and is said to breed in the Orkney

Islands, as also at Killarney, one on Mawnan Cliff, October 19th.,

1865. It has frequently been seen on and near Dartmoor, in Devonshire:

two were procured in that locality in the month of May, in the year

1831, at Estover, near the Lizard Point; one in the same year at another

place in the same county, and no doubt in many other places, and two

on the Avon. Three or four have been met with in the county of Durham-one

seen near Hartlepool-others in Sussex. In Yorkshire numerous specimens

have been at various times procured: so many that I need not here

more particularly enumerate them. One at Thorpe, near Halifax, about

the year 1867, one at Cherry Burton, near Beverley, by the keeper

of David Burton, Esq., in December, 1876. An unusual number of these

birds occurred in various parts of the country in October, 1887, also

two near Sheffield at the reservoir in September, 1883.

There is no record of the Osprey having been seen in the Hebrides.

The Osprey being so strictly a piscivorous bird, is only met with

in the immediate neighbourhood of water; but salt and fresh water

fish are equally acceptable to it; and the bays and borders of the

sea, as well as the most inland lakes, rivers, and preserves, are

its favourite resort: when young, it may even, it is stated, be trained

to catch fish.

Temminck and Wilson state that the Osprey migrates in the winter.

In Scotland, it is said to arrive in Sutherlandshire in the spring,

but, on the other hand, the specimens which have occurred on the Tweed

are recorded as having appeared there in the autumn.

The Osprey is in some degree, or rather in some situations, a gregarious

bird. As many as three hundred pairs have been known to build together

in America, which, as before remarked, seems to be by far its most

abundant habitat. It is a very frequent circumstance for several pairs

thus to congregate, the similarity of their pursuit by no means seeming

to interfere with that harmony which should ever prevail among members

of the same family. They sometimes unite in a general attack on their

common enemy, the White-headed Eagle, and union being strength, succeed

in driving him from their fishing grounds, of which they then maintain

the peaceable possession.

It would appear from the mention of the Osprey by Izaak Walton, under

the name of the Bald Buzzard, that it was formerly used in falconry.

It is naturally shy and watchful.

The flight of the Osprey, though generally slow and heavy like that

of the Buzzard, and performed with a scarcely perceptible motion of

the wings, and the tail deflected, is strikingly easy and graceful.

It rises spirally at pleasure to a great height, darts down perhaps

at times, and then again sails steadily on. When looking out for prey,

on perceiving a fish which it can strike, it hovers in the air for

a few moments, like the Kestrel, with a continual motion of its wings

and tail. Its stoop, which follows, though sometimes suspended midway,

perhaps from perceiving that the fish has escaped, or to 'make assurance

doubly sure,' is astonishingly rapid. The similar action of the Sea

Swallow may serve to give some faint idea of it.

If the fish it has pounced on be at some distance below the surface,

the Osprey is completely submerged for an instant, and a circle of

foam marks the spot where it has descended; on rising again with its

capture, it first, after mounting a few yards in the air, shakes its

plumage, which, though formed by nature extremely compact for the

purpose of resisting the wet as much as possible, must imbibe some

degree of moisture, which it thus dislodges. It then immediately flies

off to its nest with a cry expressive of success, if it be the breeding

season, or to some tree if it is not, and in that situation makes

its meal. When this is ended, it usually, though not always, again

takes wing and soars away to a great height, or else prowls anew over

the waters-unlike the other Hawks, which, for the most part, remain

in an apathetic state, the result apparently of satisfied hunger:

thus continues the routine of its daily life, as well described by

Macgillivray. Sometimes it is said to devour its food in the air,

but I cannot think this; also at times on the spot; if the fish be

too large for bearing conveniently away, the prey is held with the

head forward. The audacious White-headed Eagle often robs the too

patient Osprey of its hardly-toiled-for prey before it has had time

to devour it itself, forcing it to drop in the air, and catching it

as it falls. The Moor Buzzard and the Crow also attack him.

The sole food of the Osprey is fish, and from its manner of taking

it by suddenly darting or falling on it, it has been called by the

Italians, 'Aquila plumbina,' or the Leaden Eagle. It is however said

by Montagu that it will occasionally take other prey-that one has

been seen to strike a young wild duck, and having lost its hold of

it, to seize it again a second time before it reached the water. I

must, however, express the strongest doubt of this having been the

case. If the circumstance as described by him really occurred at all,

I can hardly think but that some other species must have been mistaken

for the one before us, particularly from the latter fact mentioned,

for Wilson, whose opportunities of observing this bird were so abundant,

says, expressly, that not only does it feed exclusively on fish, and

not on birds, but that it never attempts to seize a second time one

which it may have dropped. It usually takes its prey below the surface

of the water, and never catches it when leaping out, even when in

the case of the flying fish it has ample opportunities of doing so,

though when that persecuted creature is again submerged, it will follow

it into its more legitimate element, and take it there without scruple.

It never preys on any of the inferior land animals, which it might

so easily capture were it thus disposed. Even when the lakes, which

supply its usual food, are frozen over, and when it is difficult to

imagine how it can supply its wants without resorting to other, even

if uncongenial, food, it does not do so. It is related that sometimes

it fastens its claws so firmly in its quarry that it is not till it

has eaten a way out for them that it is set at liberty. When it visits

a pond, it 'crosses it several times at no great elevation; if he

perceives no fish, he passes on to another, and continues the pursuit

until successful.' The Rev. Grage Earle Freeman to whom I am much

indebted for several particulars as to the Falcons and Hawks, with

whose habits in falconry he made himself thoroughly well acquainted,

he expressed to me a doubt, but only guardedly, whether it may not

on some occasions take a hare or rabbit.

The Osprey seldom alights on the ground, and when it does so, its

movements are awkward and ungainly. It is not in its element but when

in the air: occasionally however it remains for several hours together

in a sluggish state of repose, perched on some mountain side, hill,

rock, or stone.

It builds at very different times, in different places-in January,

February, March, April, and the beginning of May: the latter month

appears in this country to be the period of its nidification. It repairs

the original nest, seeming, like many other species, to have a predilection

from year to year for the same building place. The saline materials

of which it is composed, and perhaps also the oil from the fish brought

to it, have the effect, in a few years, of destroying the tree in

which it has been placed. The male partially assists the female in

the business of incubation, and at other times keeps near her, and

provides her with food-she sits accordingly very close. Both birds,

when the young are hatched, share the task of feeding them with fish,

and have even been seen to supply them when they have left the nest,

and have been on the wing themselves; they both also courageously

defend them against all aggressors, both human and other. They only

rear one brood in the year. If one of the parents happen to be killed,

the other is almost sure to return, ere long, with a fresh mate: where

procured, as in other similar cases, is indeed a mystery.

The nest of the Osprey is an immense pile of twigs, small and large

sticks and branches, some of them as much as an inch and a half in

diameter-the whole forming sometimes a mass easily discernible at

the distance of half a mile or more, and in quantity enough to fill

a cart. How it is that it is not blown down, or blown to pieces by

a gale of wind, is a question which has yet to be explained. It occasionally

is heaped up to the height of from four or five feet to even eight,

and is from two to three feet or four in breadth, interlaced and compacted

with sea-weed, stalks of corn, grass, or turf; the whole, in consequence

of annual repairs and additions, which even in human dwellings often

make a house so much larger than it was originally intended to be,

not to say unsightly, becoming by degrees of the character described

above. It is built either on a tree, at a height of from six, seven,

or eight to fifteen feet, and from that to fifty feet from the ground,

on a forsaken building, or the ruins of some ancient fortress, erected

on the edge of a Highland Loch, the chimney, if the remains of one

are in existence, being generally preferred, or on the summit of some

insular crag; in fact, it accommodates itself easily to any suitable

and favourable situation. Bewick, erroneously following Willughby,

(and Mudie him,) says that the Osprey builds its nest 'on the ground,

among reeds'-it very rarely indeed does so. It is a curious fact that

smaller birds frequently build their nest in the outside of those

of the Osprey, without molestation on the one hand, or fear on the

other. Larger birds also build theirs in the immediate vicinity, without

any disturbance on the part of either.

The eggs, which are sometimes only two in number, but occasion-ally

three, and in some instances, but very rarely, as many as four, are

described by several writers, apparently following Willughby, to be

of an elliptical form. They are laid in May, and about the size of

those of a hen, and are generally similar to each other in colour,

but occasionally vary considerably in size and shape: the ground colour

is white, or dingy yellowish, or brownish white, much mottled over,

particularly at the base, in an irregular manner, with yellowish brown

or rust-colour, with some specks of light brownish grey. The larger

spots are sometimes of a very fine rich red brown.

The whole plumage of the Osprey, as before incidentally mentioned,

is very closely set, particularly on the under side, the bird almost

in this respect resembling a water fowl. Even the feathers on the

legs, unlike the long ones of the other Eagles and Hawks, partake

of this characteristic, the object of the provision being an obvious

one, on account, namely, of its frequent submersion in pursuit of

the prey on which it lives.

Weight of the male, between four and five pounds; length, about one

foot ten or eleven inches; bill, black, bluish black, or brownish

black, probably according to age, and blue or horn-colour at the base;

a blackish band runs from it backward to the shoulders; cere, light

greyish blue; iris, yellow; eyelids, white, surrounded by a dusky

ring. The rudiment of a crest is formed by the feathers of the nape,

which are lanceolate; head, white in the fully adult bird: until then,

the feathers are brown, margined with white; crown, whitish or yellowish

white, streaked with dark brown longitudinal marks; neck, white, with

a brown mark from the bill down each side; under part of the neck

brownish white, sometimes brownish black streaked with darker brown.

The nape, whitish, streaked with dark brown; chin, white, with sometimes

a few dusky streaks; throat, white or brownish white, streaked and

specked with dark or dusky brown; breast, generally white, mottled

about the upper part with a few rather light brown feathers, forming

an irregular band, and also more or less sprinkled with yellowish

or brown markings-the margins of the feathers being paler than the

rest. Selby says that the brown admixture is indicative of a young

bird, the adults generally, if not always, having that part of an

immaculate white, and there can I think be no doubt, but that it is

so. The whole plumage, especially, as above said, on the under side,

is close set, as is the case with water birds, their frequent submersions

requiring such a defence.

The back dark brown-in some individuals the feathers being margined

with a paler shade; wings, long, and of wide expanse, measuring as

much as five feet three or four inches across. The specimen shot at

Alverbank spread to the width of five feet nine inches. When closed,

they extend a little beyond the end of the tail-not quite two inches;

the first three quills are deeply notched on the inner side near the

end; primaries, dark brown, black or nearly black at the ends, the

third feather is the longest. The tertiaries assume the form of quills,

and are sometimes edged with white; larger and lesser under wing coverts,

white, barred with umber brown; tail, short and square, waved with

a darker and a lighter shade of brown above, forming six bars, and

beneath barred with greyish brown on a white ground-the two middle

feathers darker than the others; underneath, it is white between the

brown bars, and the shafts yellowish white; under tail coverts sometimes

spotted with pale rufous. The legs reticulated, and pale blue. They

are very short and thick, being only two inches and a quarter long,

and two inches in circumference-great strength being required for

its peculiar habits. They are feathered in front about one fourth

down, the feathers being white, short, and close, as above mentioned.

The toes, pale greyish blue, and partially reticulated, with a few

broad scales near the end, and furnished beneath, particularly the

outer one, with some short sharp spines, or conical scales, inclined

backward, for the evident purpose of holding fast a prey so slippery

as that which the bird feeds on. The outer toe is longer than the

inner one, the contrary being the case with others of its congeners,

and adapted for a more than ordinary turning backwards, the better

to grasp and hold a fish. The hind toe has four scales, the others,

which, as just said, are longer, and nearly equal to each other in

length, have only three. The claws, black, and nearly alike in length:

those of the first and fourth toes being larger than those of the

others.

The female is considerably larger than the male, about two feet two

or three inches or over, but the colour of both is much alike. There

is, however, in her a greater prevalence of brown over the white,

and it is of a deeper shade, approaching on the lower part of the

breast to brownish red. Weight, sometimes upwards of five pounds;

length, two feet to two feet and an inch; expanse of the wings, about

five feet and a half.

The young birds are much variegated in their plumage, which becomes

of a more uniform hue as they advance in age-the grey and the brown

giving way by degrees to white.

The young male has the feathers of the back, and the wing coverts,

bordered with white.

Variations of plumage occur in the Osprey, even in its fully adult

state; the white being more or less clear, and the brown more or less

prevalent; the legs also vary from light greyish blue, to a very pale

blue with a tinge of yellow.

"He'll be to Rome as is the Osprey To the fish

who takes by sovereignty of nature."

CORIOLANUS.