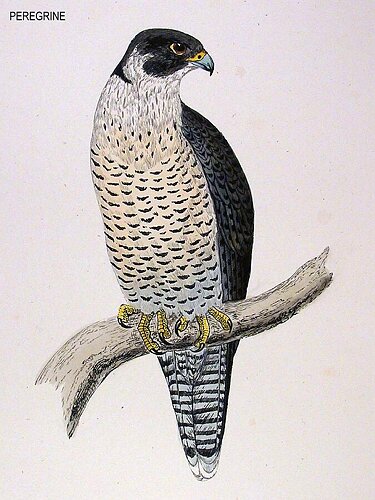

PEREGRINE-FALCON.

HEBOG TRAMOR, HEBOG GWALCH? HEBOG GWLANOG ? CAMMIN, IN ANCIENT BRITISH.

Falco peregrinus, LATHAM. FLEMING. Falco communis, LATHAM. SELBY.

Falco—To cut with a bill or hook. Peregrinus—A stranger

or foreigner— a traveller from a distant country.

The Peregrine-Falcon has always been highly prized both

living and dead, in the former case for its value in. falconry, on

account of its lofty flight, great speed, and grandeur of stoop, courageous

spirit and docility, combined with confidence and fearlessness, and

in the latter for its handsome and fine appearance. It used to be

trained for flying at Herons, Partridges, and other large birds, and

in the time of King James the First as much as a thousand pounds of

our money was once given for a well-trained 'cast' or pair. It comes

to a certain extent to know its keeper, and Mr. Knox, in his 'Game

Birds and Wildfowl,' gives a curious instance of this.—Two of

these birds trained by Colonel Johnson, of the Rifle Brigade, were

taken by him on board ship on his voyage across the Atlantic, and

were daily allowed to fly. One of them at last was lost, but, it seems,

made its way to a schooner also crossing to America, and was detained

by the captain, who refused to give it up; but on its being finally

arranged that if it showed any knowledge of its former owner he should

again have it, it most unmistakeably proved his right to it, as soon

as ever the door of the room was opened and it was brought in where

he was, flying at once to his shoulder, and showing every sign of

affection and delight. It is a bird of first-rate powers of flight,

and from its frequent exertion of those powers has derived its name.

It has very often been seen crossing the Atlantic at a great distance

from land.

The Peregrine is widely distributed, being found throughout the whole

of North America, and in parts of South America, even as far south

as the Straits of Magellan, and northwards in Greenland; in Africa,

at the Cape of Good Hope; in most countries of Europe, particularly

in Russia, along the Uralian chain, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and Lapland;

in Siberia and many parts of Asia; and also in New Holland. The rocky

cliffs of this country have hitherto afforded it a comparative degree

of protection, but 'protection' seems exploded —explosion in

fact sounding the knell of the aristocratic Peregrine.

Strange to say these birds have been known to take up a temporary

residence on St. Paul's Cathedral, in London, anything but 'far from

the busy hum of men,' preying while there on the pigeons which make

it their cote, and a Peregrine has been seen to seize one in Leicester

Square.

In Yorkshire, the Peregrine has had eyries at Kilnsea Crag and Arncliffe,

in Wharfedale, in Craven, as also near Pickering, and on Black Hambleton;

so too in the cliffs of the Isle of Wight, in which even now they

have four or five eyries, namely, Fresh-water Cliff, Main Bench, Culver

Cliff, Shanklin Chine, Black Gang Chine, and Shale Bay, as well as

in those of Devonshire and Cornwall, and it still breeds on Newhaven

Cliff, and the high cliffs which form Beechy Head, in Sussex. A pair

have been in the habit of building there for the last quarter of a

century: three young birds were taken from the nest in 1849, and came

into possession of Mr. Thomas Thorncroft, of Brighton, who in his

letter to me describes them as very docile and noble: such they are

indeed described to be by all who have kept them. Another pair built

on Salisbury Cathedral in 1879. The Bass Bock in the Frith of Forth

has been another of its breeding places; as also the Bass Rock and

the cliff on which Tantallon Castle stands; the precipice of Dumbarton

Castle; the Isle of May; the Vale of Moffat, in Dumfriesshire; many

of the precipitous rocks of Sutherlandshire; Murray Firth, the coast

of Gainrie, and the neighbourhood of Banff and St. Abb's Head; the

borders of Selkirkshire, Loch Cor, Loch Ruthven, Knockdolian, in Ayrshire,

Caithnesshire, Ailsa, Ballantrae, and Portpatrick, in Scotland; and

in Shetland it is the most common of the larger rapacious birds. In

the Hebrides it is rare—more frequent in the Orkneys; also in

Guernsey and Sark. They used to breed at Orme's Head, Llandudno, and

Bhiwleden; so too in the Isle of Man.

In Yorkshire, many of these birds have at different periods been shot,

some at Nutwell and Flamborough, also one in Home Carr Wood, near

Barnsley. One in Brackendale Wood, near Burlington, May 10th., 1856.

Three specimens have been procured in the neighbourhood of Falmouth,

of which W. P. Cocks, Esq. has obligingly sent me information; others

also. In Sussex, the Peregrine has been occasionally met with inland:

sometimes near Petworth, Burton Park, Lewes, Chichester, Arundel,

Seaford, Pevensey, Shoreham, and Rye, but seldom on the Weald. In

Kent one was shot at Doddington, Mr. Chaffey of that place informed

me, in 1849. Two curious instances of the obtaining of the Peregrine

are mentioned by A. E. Knox, Esq.: one was caught in a net with which

a person was catching sparrows from under the eaves of a barn, and

the other was shot by a farmer, after it had dashed at a stuffed wood-pigeon,

which he had fixed up in a field as a lure to decoy others within

shot. I am informed by my friend, the Rev. R. P. Alington, that it

is not uncommon in the spring in the neighbourhood of Swinhope, in

Lincolnshire. One was shot near there a few years since by Thomas

Harneis, Esq., of Hawerby House. Another at Cleethorpe by Mr. George

Johnson, of Melton Ross, and one was shot at Sutton, near Alford,

September 16th., 1857. It has also been known on Manton Common. In

Bedfordshire one was shot at Ashley wood, near Woburn Abbey, by John

White, one of the gamekeepers of His Grace the Duke of Bedford. Others

have been met with in Worcestershire—one in 1849: some on Dartmoor,

in Devonshire, and one was caught in a trap at Mutley, in 1831. In

Derbyshire one was taken on the 25th. of November, 1841, on Melbourne

Common. It was caught together with a crow in which it had stuck its

talons. It would appear, however, from the account given of it by

Mr. J. J. Briggs, to have been a trained bird that had wandered away.

One was also shot in the year 1840, near Barrow-upon-Trent; two near

Leicester in January, 1879. The Peregrine has been in the constant

habit of breeding on Caldy Island on the coast of Pembrokeshire, as

I am informed by Edward K. Bridger, Esq.; also near the Great Orme's

Head, Llandudno in Carnarvonshire, as also at Holyhead; and near St.

Anthony in Cornwall. Pennant has recorded a locality for it on the

coast of Carnarvonshire. In the Island of Hearn, Guernsey, three in

1879. In Oxfordshire at Farnborough, Aynhoe, Cropredy, and elsewhere,

the last, so far in the year 1875. Of these I have been informed by

C. M. Pryor, Esq., of The Avenue, Bedford, to whom I am also indebted

for notices of many other rare birds in that County, of which mention

will be found in these volumes.

In Ireland it has had, according to William Thompson, Esq., of Belfast,

many eyries in the cliffs of the four maritime counties of Ulster,

as well as some in other parts; in Antrim no fewer than nine, three

of them being inland, Glenariff, Salah Braes, and the Cave-hill. So

also at Mc Art's fort, three miles from Belfast, Fairhead and Dunluce

Castle, the Horn in Donegal and Knockagh hill near Carrick-fergus,

the Gobbins at the northern entrance to Belfast Bay, where two pair

built within a mile of each other—a very unusual circumstance;

likewise Tory Island, off Donegal, the Mourne Mountains in the county

of Down, Bray Head in that of Wicklow, the cliffs over the Killeries

in Galway, Bay Lough in Tipperary, the Saltee Islands, Wexford, the

Blasquet Islands, Kerry, Ardmore and Dunmore in Waterford, Howth near

Dublin, and the sea coast cliffs of the county of Cork. I had a pair

alive which came from Rathlin Island, off the north coast of Ireland.

They breed annually in Shetland and Orkney, and also occur, but less

frequently, in the Hebrides.

Whether the Peregrine is partially migratory in this country, seems

at present not to have been ascertained. It appears to be thought

that the old birds remain about their haunts, while the young ones,

after their expulsion from the nest, are compelled to wander about.

It is a shy species, and difficult to be approached. It retires to

roost about sunset, choosing the high branch of a lofty tree, or the

pinnacle of a rocky place. ' Sometimes he is seen in the open fields,

seated upon a stone, rock, or hillock, where he quietly waits, watching

for his prey.' 'He displays both courage and address in frequent contests

with his equals.'

Its flight is extremely rapid, and is doubtless well described by

Mac-gillivray, as strongly resembling that of the Rock Pigeon. It

seldom soars or sails after the manner of the Eagles and Buzzards.

It does so, indeed, occasionally, but its usual mode of flying is

near the ground with quickly repeated beating of its wings. Montagu

has calculated the rate of its flight at as much as some hundred and

fifty miles an hour, and Colonel Thornton at about sixty miles. An

average of one hundred may I think be fairly estimated. Meyer says

that it never strikes at prey near the ground, through an instinctive

fear of being dashed to pieces; but the contrary is the fact, its

upward sweep preserving it generally from this danger. The recoil,

as it were, of the blow which dashes its victim to the earth, overpowers

in itself the attraction of gravity, and it rises most gracefully

into the air until it has stayed the impetus of its flight. Instances

however have been known where both pursuer and pursued have dashed

against trees, or even a stone on the ground, in the ardour of pursuing

and being pursued, and each has been either stunned for the time,

or killed outright by the violence of the blow.

Sometimes, in pursuit of its prey, the Peregrine will ' tower'' upwards

until both are lost to sight. In the breeding season also, both birds

may now and then be seen soaring and circling over the place chosen

for the nest, and at this period they will seize and hold and convey

off to their young the prey they have struck, not dashing it to the

ground, a quarry not too large being accordingly singled out. They

will at times attack even the Eagle. On alighting they often quiver

the wings and shake the tail in a peculiar manner, and when standing

frequently nod or bow down the head quickly. They are fond of basking,

lying down at full length on the ground, and at times resting in a

perfectly sitting posture, with the legs flat under them.

The food of the species before us consists principally of birds such

as the larger and smaller sea-gulls, auks, guillemots, puffins, larks,

pigeons, ptarmigan, rooks, jackdaws, woodcocks, land-rails, wild geese,

and even at times the Kestrel, partridges, plovers, grouse, curlews,

teal, and ducks; but it also feeds on hares, rabbits, rats, and other

small quadrupeds, as well as at times on larger ones, such it is said,

though but seldom, as dogs and cats, and also occasionally, it has

been stated, on fish. It appears to have an especial 'penchant' for

the snipe. The plumage of its feathered game is carefully plucked

off before they are eaten. It is said to harass the grey crows, but

not to use them for food. Some cases have been known of Peregrines

having fallen into the sea, and been drowned, together with birds

which they had struck when flying over it: the more remarkable as

the prey so seized were only small, and far inferior in size to themselves:

probably they had been in some way hampered or clogged,

as a good swimmer may be by a drowning boy, so that although if they

had fallen on the land, they might have extricated themselves, yet

such opportunity has been lost by their mischance of dropping into

the sea, and they have met with a watery grave. It is said that in

general they abstain from striking their game over water, in view

of such a slip. They are more successful, as might be supposed, in

chasing a quarry up the side of a hill or mountain than downwards,

the latter case giving the bird of inferior power of flight a comparative

advantage. A black grouse, a bird equal to itself in weight, if not

heavier, has been found in the nest of one of these Falcons, with

which it had probably flown several miles. Sometimes, if it finds

a bird which it has struck down too heavy to carry away, it will drop

it, and seek another in its stead. It seldom visits the poultry yard.

It is said to overpower even the Capercailie. Its clutch is less fatal

than its stroke: it has been known to bear away birds for a long distance

in its claw, without serious injury.

This bird has frequently been seen to stoop upon and carry off game

immediately before sportsmen, both such as had been shot at and killed,

and others which were being followed. It takes its prey as well by

pursuit, as by a sudden descent upon it. It seldom follows it into

cover. Sometimes, for what reason it is impossible to say, it has

been known to strike down several birds in succession, so at least

I have seen it stated; before securing one for its food. One instance

however is recorded where having killed, and being in the act of devouring

one bird, it chased and caught another of the same kind, still holding

the former in one claw, and securing the latter in the other. The

Peregrine has been known to cut a snipe in two, and in like manner

to strike off the head of a grouse or pigeon, 'at one fell swoop.'

The sound of the buffet may be heard at a considerable distance. It

is said that all the Falcons crush and destroy the head of their prey

before devouring them. The Peregrine will, as I have already mentioned,

occasionally kill and eat the Kestrel, though a bird of its own tribe.

In confinement it has been known to do the same, and on one occasion

to devour a Merlin, which it had slain. Two instances are recorded

also of their killing and eating their partners in captivity. On both

occasions the female was the cannibal, but in the latter of the two

she died a few days afterwards, from the effects of the wounds she

had received from the male in his self-defence. They soon become quite

at home in confinement.

It is very curious how these and all the others birds which form the

food of the one before us, live in its immediate vicinity, without

any apparent fear or dread. They seem patiently to 'bide their time,'

and

take their chance of being singled out from their fellows. Perhaps

with equal wisdom to that of the followers of the Prophet, they are

believers in fatalism, and, content with the knowledge that whatever

is, is, and whatever will be, will be, live a life of security, and

resign it at the 'fiat' of the Peregrine, as a matter of course. This

applies to cases where both are residents together; where however,

strange to say, the Peregrine is only a straggling visitor, his presence

but for a day or two has the effect of dispersing the flocks of birds

which had been peacefully enjoying themselves before his arrival.

Its mode of striking its prey has been variously described. It has

by many been supposed to stun its victim by the shock of a blow with

its breast, and by others it has been known to rip a furrow in its

quarry completely from one end of the back to the other, with its

talons, not the bill. In the former case it is said to wheel about,

and return to pick up the quarry it has struck. It is, as may be supposed,

the terror of all it pursues, which, rather than venture again on

the wing while it is in the neighbourhood, will suffer themselves

to be taken by the hand.

In the pursuit of birds near the sea, the Peregrine frequently loses

them by their seeking refuge on the water, where they are safe for

the time from his attack. If they leave it for the land, they are

again pursued, and most interesting chases of this kind have often

been witnessed : they end either in the Hawk catching the bird before

it can reach the water, or in its being tired out by its perseverance

in thus keeping him at bay. Conscious of the disadvantage it is at

on this element, it but very rarely indeed attempts to seize prey

when upon it; it has however been known to carry off a razor-bill

or guillemot from a flock in the water, and bear it away to its nest.

The mention of this bird may introduce the following anecdotes related

by Montagu:—'A writer in a popular periodical describes one

pursuing a razor-bill, which instead of assaulting as usual with the

death-pounce of the beak, (This is a mistake; the quarry is struck

with the talons always,) he seized by the head with both his claws,

and made towards the land, his prisoner croaking, screaming, and struggling

lustily; but being a heavy bird, he so far over-balanced the aggressor,

that both descended fast towards the sea, when just as they touched

the water, the Falcon let go his hold and ascended, the razor-bill

as instantaneously diving below.' A sea-gull has been known to beat

a Peregrine in a fair flight, baffling him by its frequent turnings,

in the same way that a white butterfly by its zigzag motion escapes

a sparrow.

Feeding as the Hawks do, on birds and animals, they have the habit,

partaken of likewise by several other genera of birds, of casting

up the indigestible part of their food, which in the present case

consists of fur and feathers, in small round or oblong pellets.

The note of the Peregrine is loud and shrill, but it is not often

heard except in the beginning of the breeding season.

It builds early in the spring. The young are hatched about the first

week in May. If one bird is shot, the other is sure to return with

a fresh mate, and that without loss of time, generally within the

brief space of twenty-four hours. Who can explain the instinct that

guides the widower or widow, or trace the hand of the overruling power

that supplies the loss? A female bird which had been kept in confinement,

has been known to pair with a wild male. She was shot in the act of

killing a crow, and the fact was ascertained by a silver ring round

her leg, on which the owner's name was engraved. The female while

sitting is heedless of the appearance of an enemy, but the male, who

is on the look out, gives timely notice of any approach, signifying

alarm both by his shrill cry and his hurried flight. They defend their

young with much spirit, and when they are first hatched, both birds

dash about the nest, in such a case, in manifest dismay, uttering

shrieks of anger or distress: at times they sail off to some neighbouring

eminence, from whence they descry the violation of their hearth, and

again urged by their natural 'storge,' re-approach their eyrie, too

often to the destruction of one or both of them. In either case, however,

the situation being a good one, and having been instinctively chosen

accordingly, is tenanted anew the following spring, by the one bird

with a fresh mate, or by a new pair: the same situation is thus resorted

to, year after year. In the latter part of autumn, when the young

birds' education has been completed, so that they are able to shift

and forage for themselves they are expelled by the old ones from the

parental domain, as with the homely robin. The young are sometimes

fed by the one bird dropping prey from a great height in the air to

its partner flying about the nest, by whom it is caught as it falls.

It would appear that both birds sit on the eggs.

The nest, which is flat in shape, is generally built on a projection

or in a crevice of some rocky cliff, sometimes in Church towers. It

is composed of sticks, sea-weed, hair, and other such materials. Sometimes

the bird will appropriate the old nest of some other species, and

sometimes be satisfied with a mere hollow in the bare rock, with occasionally

a little earth in it. It also builds in lofty trees.

A simple but ingenious way of catching the young of these and other

Hawks, is mentioned by Charles St. John, Esq., in his entertaining

'Tour in Sutherlandshire.' A cap, or 'bonnet' is lowered

'over the border' of the cliff, down upon the nest; the young birds

strike at, and stick their claws into it, and are incontinently hauled

up in triumph.

The eggs are two, three, four, or, though but rarely, five in number,

and rather inclining to rotundity of form. Their ground colour is

light russet red, which is elegantly marbled over with darker shades,

spots, patches, and streaks of the same, or freckled with dull crimson,

or deep orange brown; sometimes with a tint of purple, or the end

is thus marked, the remainder being the ground colour of pale yellowish

white. As many as four young have been taken from one nest. When this

is the case, one is generally much smaller than the rest. In one instance,

however, all four were of equal size; and, moreover, which is still

more unusual, and perhaps accounts for the fact just mentioned, all

females—a proportion being generally preserved. Incubation lasts

three weeks.

The Peregrine varies more in size than perhaps any other bird of prey;

sometimes it is nearly equal to the Jer-Falcon. It varies also in

colour, but the band on the sides of the throat is a permanent characteristic.

Its whole plumage is close and compact; more so than that of any other

British species of Hawk. It is a stout and strong-looking bird.

Male, weight, about two pounds; the Eev. Charles Hudson, of Marton

Hall, near Burlington, wrote me word of one, perhaps a female, shot

at Buckton in April, 1879, which weighed two pounds and a half. Length,

from fifteen to eighteen or twenty inches; bill, bluish black at the

tip, and pale blue at the base; cere, dull yellowish; iris, dark hazel

brown; the feathers between the bill and the eye are of a bristled

character; head, bluish black, sometimes greyish black, and at times

brownish black; neck, bluish black behind, more or less white in front,

in some specimens with, and in others without spots: a dark streak

of bluish black from the mouth, often called the moustache, divides

it above; chin and throat, white or pale buff colour; breast, also

above, white, cream white, or rufous white according to age, the white

being the later state, mottled with spots and streaks; below and on

the sides, ash grey, lined lengthways, and barred across with dark

brown; back, deep bluish grey or slate-colour, shaded off into ash

grey, and more or less clearly barred with greyish black: some specimens

are darker, and others lighter, according to age, the bars becoming

narrower as the bird gets older.

The wings are very long and pointed, extending when closed to from

an inch to within nearly half an inch of the end of the tail: the

second quill is the longest, and the first nearly as long, the third

a little shorter;

greater and lesser wing coverts, bluish grey, barred as the back;

primaries and secondaries, dark ash-coloured brown, barred on the

inner webs with lighter and darker rufous white spots, and tipped

with dull white; tertiaries, ash-colour, faintly barred; greater and

lesser under wing coverts, whitish, barred with a dark shade. The

tail, slightly rounded, bluish black, or bluish, tinged with yellowish

grey, barred with twelve bars of blackish brown, the last the widest,

and the others gradually widening towards it; upper tail coverts,

bluish black, barred as the back; under tail coverts, ash grey, barred

with dark shades; legs, dull yellow, short and strong, feathered more

than half-way down, and scaled all round; the scales in front being

the largest; toes, dull yellow, very long, strong and scaled, and

rough beneath; the second and fourth are nearly equal, the hind one

the shortest, the third the longest, and the third and fourth united

by a membrane at the base; claws, brownish black or black, strong,

hooked, and acute. When perched the birds often sit with the inner

toes of each foot crossed the one over the other.

The female is larger by comparison with the male than even is the

case with other Hawks. The dark parts of the plumage are darker, and

the dark markings larger: I have seen one nearly black in general

appearance, they decrease with age. Length, from nineteen to twenty-three

inches; cere, dull yellow; iris, dark brown, space surrounding the

eyes dull yellow; head, deep greyish brown; neck, in front yellowish

white, with longitudinal marks of deep brown, and on the sides and

behind greyish brown; the streak on the sides is dark brown; throat,

yellowish white, marked longitudinally like the neck; breast, brownish

white, or yellowish white, with bars of deep brown or greyish black;

it is altogether more inclined to rufous than in the male, with less

grey; the longitudinal spots come higher up, and the transverse spots

and bars are broader and more boldly marked, and deeper in hue: back,

deep brownish grey, or bluish grey, barred less distinctly than in

the male with grey.

The wings expand to the width of three feet eight or nine inches,

the quill feathers are of a deep greyish brown or brownish black colour,

or varying as the back, spotted on the outer webs with ash grey, and

on the inner ones with cream-colour; the first quill has a deep indentation

near the tip of the inner web; greater and lesser wing coverts, blackish

brown, with bars of grey on the outer webs, and spots of reddish white

on the inner; secondaries, tipped with whitish; greater and lesser

under wings, coverts white, barred with black. The tail has eighteen

bars of ash grey and deep brown alternately; those of the latter colour

are the broader; the tip is brownish white; the bars on the tail are

more distinct than in the, male bird. Upper- tail coverts, bluish

grey, barred with greyish black.

The young are at first covered with white down: when fully fledged

the bill is dull pale blue, darker at the tip; cere, greenish yellow;

iris, dark brown. Forehead and sides of the head, yellowish white,

or pale rufous; head on the crown, blackish brown, with a few white

feathers at the back; neck, behind, yellowish white with dusky spots;

chin, yellowish white; throat, white; the band on the side of it blackish

brown; breast, reddish white, or pale reddish orange, darkest in the

middle, with longitudinal markings of a dark blackish brown colour,

and the centre of each feather the same; back, brownish black shaded

with grey, the feathers edged with pale brown or rufous. The quill

feathers of the wings are blackish brown, spotted with brownish white

on the inner webs, and tipped with the same; tail, blackish or bluish

brown, barred and tipped with brownish red, or reddish white, greyish

towards the base; legs and toes, greyish or greenish yellow: as the

bird advances towards maturity a bluish shade becomes observable on

all the upper parts, while the lower parts become more white, and

the dark markings smaller, as well as more inclined transversely than

longitudinally.

Sir William Jardine describes a variety in a state of change, as having

the upper parts of a tint intermediate between yellowish brown and

clove brown. The tail, instead of being barred, had an irregular spot

on each web of ochraceous where the pale bands should be, and the

longitudinal streakings of the lower parts wood brown, instead of

the deep ruddy umber brown seen generally in the young.

"Who checks at me to death is dight."

Marmion.