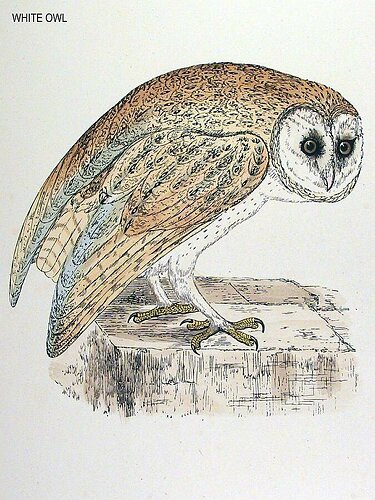

WHITE OWL,

DILLYAN WEN, IN ANCIENT BRITISH.

YELLOW OWL. BARN OWL. SCREECH OWL. GILLI-HOWLET. HOWLET. MADGE OWL.

CHURCH OWL. HISSING OWL.

Strix flammea, PENNANT. MONTAGU. Aluco flammeus, FLEMING. Aluco minor,

ALDROVANDUS.

Strix—Some species of Owl. Flammea—Of the colour of flame—tawny

—yellow.

This bird, a ' High Churchman,' is almost proverbially

attached to the Church, within whose sacred precincts it finds a sanctuary,

as others have done in former ages, and in whose ' ivy-mantled tower'

it securely rears its brood. The very last specimen but one that I

have seen was a young bird perched on the exact centre of the ' reredos'

in Charing Church, Kent, where its ancestors for many .generations

have been preserved by the careful protection of the worthy curate,

my old entomological friend, the Rev. J. Dix, against the machinations

of mischievous boys, and the ' organ of destructive-ness' of those

who ought to know better.

The White Owl is dispersed more or less generally, according to naturalists,

all over the earth: it is however the least numerous in the colder

districts. Northward it occurs from Germany as far as Denmark and

Sweden, but is as yet unrecorded as an inhabitant of Norway. In Africa,

its range extends southward to the Cape of Good Hope, and from there

to Quillinane on the one side, and to Angola on the other. In Asia,

eastward, to Mesopotamia, India, and New Holland, as is said; and

westward, if indeed the species be the same, to the United States.

Madeira is one of its habitats, and it also occurs in the Azores:

in Tartary it is stated to be very abundant. It occurs throughout

England, and that as the most plentiful of its tribe; in Ireland it

is likewise the most common of the Owls; in Scotland it is less numerous,

particularly towards the north-west; and in the Orkney Islands still

more unfrequent. In the Hebrides, it has been traced in Mull and Islay.

This bird is a perennial resident with us, and if unmolested frequents

the same haunts for a succession of years; the young, no doubt, in

time, taking the place of the old. In Yorkshire, in the neighbourhood

of Barnsley it occurs, or has occurred; also near Huddersfield, Halifax,

and Hebden-Bridge, but of course in these parts much less frequently

than in those districts of the county where the quiet tranquillity

of rural life is undisturbed by the bustle of business, and peace

prevails over turmoil, happiness over the misery of money-making,

the country over the town, GOD over the Enemy of man. It displays

considerable affection for its young. Mr. Thomas Prater, of Bicester,

relates in the ' Zoologist,' that an old ivy-clad tree having been

blown down at Chesterton, Oxfordshire, a family of White Owls was

dislodged by its fall: the parent bird placed the young ones under

the tree, and was not deterred from her maternal duties by the frequent

visits of the keeper on his rounds, but one morning as he was turning

away from looking at them, flew at him with great fury, and buffeted

him about the head.

As a proof, among the many others which have been, and might be given,

of the influence of protection and kindness upon wild birds, I may

here mention, my informant being Mr. Charles Muskett, of Norwich,

that a pair of this species, which lived in a barn near his father's

residence, were so fearless that they would remain there while the

men were thrashing, and if a mouse was dislodged by a sheaf being

removed, would pounce down upon it before them, without minding their

presence. They not very unfrequently become of their own accord half-domesticated,

from frequenting the vicinage of man without molestation, where their

good services are appreciated, and their presence accordingly is encouraged.

These birds indeed are very tameable, and will afterwards live in

harmony with others of various species. Montagu kept one together

with a Sparrow-Hawk and a Ringdove; at the end of six months he gave

them all their liberty— the Owl alone returned—the others

preferred their native freedom to the acquired habits of domestication.

Another which escaped from the place of its captivity, came back in

a few days voluntarily to it. The movements of this bird, when they

can be closely observed, are very amusing: standing on one leg, it

draws the other up into its thick plumage, and if approached, moves

its head awry after the manner of a Chinese mandarin, or falls down

flat on its side, like Punch in the puppet-show. To be properly tamed

they must be taken young: education, as is the case with the ' bipes

implume,' is much less difficult then than afterwards. They will come

to a whistle, or answer to their name, and settle on the shoulder

of whomsoever they may be acquainted with. They take notice of music,

and appear to be fond of it.

Bishop Stanley says, 'a friend of ours had taken a brood of young

Owls, and placed them in a recess on a barn-floor, from whence, to

his surprise, they soon disappeared, and were again discovered in

their original breeding-place. Determined to solve the mystery of

this unaccountable removal, he placed them on the barn-floor, and

concealing himself, watched their proceedings, when to his surprise

he soon perceived the parent birds gliding down, and entwining their

feet in the feet of their young ones, flew off with them to their

nest. To confirm the fact without a doubt, the experiment was often

repeated, in the presence of other witnesses.'

One of these birds after having been tamed for some time, was found

to be in the habit for some months, of taking part of its food to

a wild one, which overcame its shyness so far as to come near the

house, and it would then return to the kitchen, and eat the remainder

of its portion. Another of them is described by Meyer, as so tame

'that it would enter the door or window of the cottage, as soon as

the family sat down to supper, and partake of the meal, either sitting

upon the back of a chair, or venturing on the table; and it was sometimes

seen for hours before the time watching anxiously for the entrance

of the expected feast. This exhibition was seen regularly every night.'

If captured when grown up, it sometimes refuses food, and its liberty

in such, indeed in any case, should be given it. In cold weather a

number of these birds have been found sitting close together for the

purpose of keeping each other warm. The male and female consort together

throughout the year. If aroused from their resting-place during the

day, they fly about in a languid, desultory manner, and are chased

and teased by chaffinches, tomtits, and other small birds, by whom

indeed they are sometimes molested in their retreat, as well as by

the urchins of the village.

The flight of this bird, which is generally low, is pre-eminently

soft, noiseless, and volatile. It displays considerable agility on

the wing, and may be seen in the tranquil summer evening when prowling

about, turning backward and forward over a limited extent of beat,

as if trained to hunt, as indeed it has been—by Nature. It also,

its movements being no doubt directed by the presence or absence of

food, makes more extended peregrinations in its 'night-errantry.'

If its domicile be at some distance, it flies regularly at the proper

time, which is that of twilight, or moonlight, or when 'the stars

glimmer red,' to the same haunt. During the day it conceals itself

in hollow trees, rocks, buildings, and evergreens, or some such covert,

but has been known to hunt even in the afternoon. It is a bird of

a cultivated taste, preferring villages and towns themselves, as well

as their neighbourhoods, to the mountains or forests, and frequents

buildings, church steeples, crevices and holes in walls, for shelter

and a roosting place, as also, occasionally, trees and unfrequented

spots. Montagu says that it sometimes flies by day, particularly in

the winter, or when it has young. It certainly does so. When at rest

it stands in an upright position.

Moles, rats, shrews, mice, and nestlings, are extensively preyed on

by the bird before us: as many as fifteen of the latter have been

found close to the nest of a single pair, the produce of the forage

of one night, or rather part of the produce, for others doubtless

must have been devoured before morning. He who destroys an Owl is

an en-courager of vermin—nine mice have been found in the stomach

of one—a veritable 'nine killer.' It is very interesting to

watch this bird, as I have had much pleasure in doing, when hunting

for such prey, stop short suddenly in its buoyant flight, stoop and

drop in the most adroit manner to the earth, from which it for the

most part speedily re-ascends with its booty in its claws; occasionally,

however, it remains on the spot for a considerable time, 'and this,'

says Sir William Jardine, 'is always done at the season of incubation

for the support of the young.' It also occasionally eats small birds—thrushes,

larks, buntings, sparrows, and others, as also beetles and other insects.

It has been known to catch fish from shallow water. A tame one kept

in a large garden, killed a lapwing, its companion.

Mr. Waterton argues that Owls cannot destroy pigeons, or the pigeons

would be afraid of them as they are of hawks, but this is not quite

conclusive, for as shown in previous articles, pigeons and other small

birds become habituated to the presence of Hawks, and the latter,

as it would seem, to theirs, so that both parties dwell together in

amity as much as the Owls and pigeons, from acquired habit or natural

instinct. In seven hundred and six pellets cast up by some of these

birds, there were found the remains of twenty-two small birds, viz:

nineteen sparrows, one greenfinch, two swifts, sixteen bats, and two

thousand five hundred and twenty mice, voles, and shrews, and three

rats.

'A person,' says Bishop Stanley, 'who kept pigeons, and often had

a great number of young ones destroyed, laid it on a pair of Owls,

which visited the premises, and accordingly, one moonlight night,

he stationed himself, gun in hand, close to the dove-house, for the

purpose of shooting the Owls. He had not taken his station long, before

he saw one of them flying out with a prize in its claws; he pulled

the trigger, and down came the poor bird, but instead of finding the

carcase of a young pigeon he found an old rat, nearly dead.' These

Owls feed on shrew-mice, though rejected by cats and other animals,

on account, as is supposed, of their disliking either their taste

or smell; but it would seem that they do not prefer them, for the

Eev. Leonard Jenyns has observed that shrews are repeatedly found

whole beneath the nest, as if cast out for the like reason, and I

cannot help thinking that the very frequent occurrence of these mice

dead on pathways in fields which every one must have observed, may

be attributable to the same cause. Fish are also occasionally, as

above mentioned, the prey of this species of Owl, as well as of others;

possibly at times of all. It has been suggested that the glare of

their eyes may be a means of attracting the fish within their reach,

but I must place this fancy in the same category with another which

I have alluded to under the head of the Snowy Owl. Not to mention

that other birds, such as the Osprey and Fishing-Eagle, which take

fish in the same manner, by pouncing on them, find them ready to their

claw without the need of any attractive influence, and that Owls see

as well at the time they fly, as the Osprey at the time that it does,

and that fish, as every fly-fisher is aware, keep the same general

positions by night that they do by day, it may be remarked, as those

who have engaged in 'Barbel-blazing' in the river Wharfe well know,

that though certain fish may sometimes be attracted more or less by

light, as the salmon, yet that they are not necessarily so, for that

the light oftentimes seems to keep them pertinaciously at the bottom

of the stream. Besides, how is the instantaneous catching of the fish

by the Owl to be effected ? They are caught from the middle of the

pool—Is the Owl to keep hovering over them after the manner

of the Kestrel, until they have time to ascend from the depth and

answer to the wooing of his eyes, inviting them in the language of

Mrs. Bond to her ducks, '0! will you, will you, wont you, wont you,

come and be killed?' 'You may call spirits from the vasty deep,' says

Shakespeare, 'but will they come when you do call them V and I am

inclined to think that the fishes will be found in their deep, at

least as deaf, or rather as blind to such an invitation.

The White Owl is said to collect and hoard up food in its place of

resort, as a provision against a day of scarcity. It seizes its prey

in its claw, and conveys it therein, for the most part, when it has

young to feed; one however has been seen to transfer it from its claw

to its bill while on the wing; but, as Bishop Stanley observes, 'it

is evident that as long as the mouse is retained by the claw, the

old bird cannot avail itself of its feet in its ascent under the tiles,

or approach to their holes; consequently, before it attempts this,

it perches on the nearest part of the roof, and there removing the

mouse from its claw to its bill, continues its flight to the nest.

Some idea may be formed of the number of mice destroyed by a pair

of Barn Owls, when it is known that in the short space of twenty minutes

two old birds carried food to their young twelve times, thus destroying

at least forty mice every hour during the time they continued hunting,

and as young Owls remain long in the nest, many hundreds of mice must

be destroyed in the course of rearing them. Of seven hundred and six

pellets of a pair of these birds, the component parts were the remains

of fifteen hundred and nine shrews, twenty-two small birds, sixteen

bats, three rats, two hundred and thirty-seven mice, and six hundred

and ninety-three field mice.

The note of this species is a screech—a harsh prolongation of

the syllables 'tee-whit,' and it seldom, if ever, hoots. It has too

an ordinary hiss, uttered both when perched, and in flight; and it

also makes a snoring sort of noise when on the wing. It has been asserted

that it never hoots, but 'never's a bold word,' Sir William Jardine

is not the man to misstate a fact. What if the White Owl should be

to be added to the number of mocking birds ? The Rev. Andrew Matthews'

reasoning on this subject is somewhat obscure: he is of opinion that

the White Owl does not hoot, and in corroboration thereof, says that

while a tame Brown Owl lived, the large trees round the house were

nightly the resort of 'many wild birds of this species,' who left

no doubt about their note, but after his death, though the screeching

continued, the hooting ceased.

If attacked, these birds turn on their backs, and snap and hiss. The

young while in their nest make the said odd kind of snoring noise,

which seems to be intended as a call to their parents for food.

"So a fond pair of birds, all day, Blink in their nest, and doze

the hours away."

The White Owl builds for the most part, in old and deserted, as well

as in existing buildings and ruins, chimneys, eaves, or mouldering

crevices, barns, dove-cotes, church steeples, pigeon lofts, and, but

very rarely, in hollow trees, also in rocks, when or where none of

the former are to be had. With the pigeons, if there are any in the

place, they live in the most complete harmony, and often unjustly

bear the blame of the depredations committed by jackdaws and other

misdemeanants, both quadruped and biped.

The nest, if one be made at all, for oftentimes a mere hollow serves

the purpose, is built of a few sticks or twigs, lined with a little

grass or straw, or, though but seldom, with hair or wool, and this

is all that it fabricates, and to but a small extent either of bulk

or surface.

The eggs are white and of a round shape, generally two or three, but

sometimes as many as four, five, or six in number, which may be accounted

for by the ascertained fact that they will sometimes lay a first,

second, and third clutch of two eggs each, so that one or both of

the latter may be hatched before the first brood leaves the nest,

and thus birds in even three stages of growth may be fed and fostered

at one and the same time, the successive broods coming on 'imparl

passu.' It will be seen that I have before alluded to something of

the sort, and I shall have a most extraordinary circumstance of the

kind to narrate, 'in loco,' of the Moorhen. An egg has been known

of an oval shape, and much lengthened. The young have been found in

the nest in the months of July and September. Mr. Waterton has known

a young brood hatched in September and December, but the end of April,

May, or June, is the more proper time. A pair observed by the Rev.

John Atkinson, of Layer Marney Rectory, Kelvedon, Essex, for four

successive years, ordinarily reared four young, but had not more than

one brood in the year. The remarks I have before made about the dispersion

of birds is borne out by his observation, that 'the old birds remained,

but the young ones seemed to leave the immediate neighbourhood,' and

again, in the list of the birds of Melbourne, Derbyshire, by J. J.

Briggs, Esq., he says, writing of this same species, 'hundreds of

individuals have been reared in this spot, but it is never occupied

by more than one pair at the same time, for no sooner is' a brood

fully fledged and able to maintain itself, than a pair of the strongest

drive the rest of the family from the spot, and occupy it themselves.'

The appearance of this Owl, owing to its somewhat wedge-shaped face,

is very singular, especially when asleep, as it is then even more

elongated. The whole plumage is beautifully clean and pure, and most

elegantly flecked with small markings. Old birds become yet more white

if possible. Male; weight, about eleven ounces; length, about one

foot one inch, or a little more; bill, yellowish pink, yellow in the

fully adult bird, and almost white in old age; cere, flesh-coloured;

iris, deep brown, or bluish black, but its general aspect is dark

as 'berry bright.' it is only opened a little laterly during the day,

but quite round at night; there is a slight tinge of reddish brown

round the inner corner of the eye. Head, pale buff, thinly spotted

with black and white; the ends of the feathers are tinted with pale

grey, and the tips marked zigzag with dark purple and black and white

spots; crown delicately barred with waves of pale grey and dull yellow,

and it is darker or lighter in different individuals, the tips of

the feathers with fine zigzag lines and black and white spots; neck,

pure silky white, sometimes tinged with delicate yellow or buff, and

small brown spots; the ruff the same, but often marked on the upper

part with yellowish or darkish tips to the feathers; sometimes the

upper part and the lower alternate these colours 'vice versa,' and

sometimes it is yellowish all round; nape, pale buff, thinly spotted

with black and white. Chin, throat, and breast, pure silky white:

back, buff, thinly spotted with black and white, and a shade darker

than the head: different specimens have more or less buff and grey.

The wings extend about half an inch beyond the tail, and expand to

the width of three feet or over, the first quill feather is rather

shorter than the second, which is the shortest in the wing; greater

and lesser wing coverts, beautifully spotted with white, like a string

of pearls; primaries, buff on the outer webs, paler on the inner,

edged with white, or altogether white, and barred or spotted with

alternate black and white, both freckled over: beneath they are yellowish

white; towards the ends the dark bars shew faintly through; the second

feather is the longest, the first nearly as long; secondaries, pale

buff, barred or spotted irregularly in like manner with two white

and two grey spots on each side of the shafts; tertiaries, buff and

spotted: all the quills are pure white on three fourths of the breadth

of their inner webs; greater and lesser under wing coverts, white,

sometimes pale buff with small dark spots. Tail, pale buff, with four

or five blackish grey bars; the tip white; the side feathers almost

entirely yellowish white, as are the inner webs of all the feathers

except the two middle ones; it is even, but jagged at the end as are

the wings; tail coverts, buff and spotted; legs, feathered with short,

white, or sometimes very light rufous hairlike feathers, shortest

near the toes, which are flesh-coloured, but covered above with the

feathers of the legs; claws, pale brown, or yellowish white, thin

and much pointed; that of the middle toe slightly serrated on the

inner side, and all more or less grooved beneath. They become whitish

in age.

The female resembles the male, but the colours are duller, and the

breast is often marked with the yellowish grey of the back, and spotted

on the tips of the feathers at its lower part with greyish black.

Length, one foot three inches and a half; the wings expand to the

width of three feet two inches or over.

The young birds are at first covered with snow-white down; the yellow

plumage is gradually assumed, being at first paler in colour than

in the old birds, and the breast less tinged with it, but being considerably

like the old ones; there is not much change as they advance in age.

It is long before they are able to fly. When fully fledged the length

is about twelve inches; the bill, pale flesh-colour; iris, black;

there is an orange brown spot before it; the face is dull white, the

ruff white, its tips rufous; breast, white; back, pale reddish yellow,

mottled with grey and brown as in the adult; primaries, light yellowish

tinged with grey, and only a little mottled. Tail, light yellowish

grey and mottled, and but faintly barred; claws, pale purple brown.

Varieties of this bird have occasionally occurred. Meyer mentions

one which was pied yellow and white; another, of which the ground

colour was perfectly white, and the pencillings on the upper plumage

very indistinctly defined in the palest possible colouring. Some are

much more darkly coloured than others. Another had all the breast

of a rich buff colour, the face, as I may well call it, white, the

head and back several shades darker than the normal tint.

"Save that from yonder ivy-mantled tower

The moping Owl doth to the moon complain

Of such, as wandering near her sacred bower,

Molest her ancient solitary reign."

GRAY.