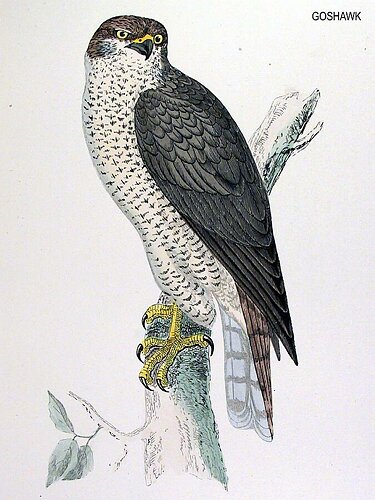

GOSHAWK.

HEBOG MAETHIN, IN ANCIENT BRITISH.

Astur palumbarius, SELBY. GOULD. Falco palumbarius, PENNANT. MONTAGU.

BEWICK.

Buteo palumbarius, FLEMING. Accipiter palumbarius, JENYNS.

Astur—A species of Hawk, {Julius Firminius Maiernus) conjectured

from Asturia, in Spain. Palumbarius. Palumba—A Pigeon.

This species occurs in Europe, Asia, Africa, and perhaps

in America; in the former, it has been known in Holland, Denmark,

Norway, Portugal, Spain, Turkey, Greece and its islands, the latter

in winter, Lapland, Russia as far as Kamschatka, Sweden, Germany,

France, Italy, and Switzerland; in Asia, in China, Tartary, India,

Palestine, Persia, and Siberia; and also in North America; and North

Africa, in Algeria, according to some opinions.

The Goshawk, though a short-winged species, and differing therefore

in its flight from those most esteemed in falcomy, was highly valued

in that art, and flown at hares and rabbits, pheasants, partridges,

grouse, ducks, geese, herons, and cranes.

In Yorkshire, the first occurrence of this bird on record was at Cusworth,

near Doncaster, where one was killed in the year 1825, by the gamekeeper

of W. B. Wrighton, Esq., M.P. One since near Driffield, in February,

1852. Another at the end of January, 1877, at Flam-borough, by a keeper

of the Rev. Y. G. Lloyd-Greame, of Sewerby House. A fine specimen

in immature plumage was shot at Westhorpe, near Stowmarket, in the

county of Suffolk, on the 20th. of November, 1849. An adult male had

been trapped by a gamekeeper in the same county, in the month of March,

1833, three others also of late years, and in November in the same

year, another was obtained in the adjoining county of Norfolk: it

had alighted on the rigging of a ship, and was brought into Yarmouth.

An immature male Goshawk was killed near Bellingham, in Northumberland,

in the month of October in the same year. A very fine female was shot

at Bolam Bog, in the same county, on the 18th. of February, 1841.

Another female near the Duke of Northumberland's Park, at Alnwick,

in the same year; and again a fourth, also a female, was caught in

a trap near Beddington, by the gamekeeper of Michael Langridge, Esq.

: two others also. In Nottinghamshire it has occurred at Rufford in

1848. Also in Oxfordshire at Wroxton, Hanwell, and other places. Five

examples in Suffolk, and eleven in Norfolk, have been recorded within

some years. Dr. Moore records it as having been occasionally on Dartmoor,

in Devonshire. One was caught near Egham, in Surrey, early in the

year 1816, in the following curious manner:—It was perched upon

a gate-post, so intently engaged in watching a flock of starlings,

that it did not perceive the approach of a man who came behind it,

and took it by its legs.

In the Orkney Islands it is not very unfrequently seen, according

to Mr. Low in his 'Fauna Orcadensis,' and also Mr. Forbes : if the

fact be so, it most probably occurs in the Hebrides also, but Mr.

Yarrell doubts whether the Peregrine may not have been mistaken for

it. So too in Shetland. In Ireland, Mr. Thompson, of Belfast, says

that it cannot be authentically determined to have occurred, but it

is since reported to have been met with at Longford, a male bird,

and one in the County of Wicklow. In Scotland it seems to be indigenous,

particularly in the central parts, in the Grampians of Aberdeenshire;

and this account is confirmed by others as stated by Mr. St. John;

and of his own knowledge in the forest of Darnaway; on the rivers

Spey and Dee, where it has been said by Pennant to breed, and in the

forest of Rothiemurcus, where it was known to do so, and in Glen-more.

One was killed near Dalkeith; also in Caithness-shire. Some seven

examples or more are on record, and it seems to have bred recently

in Kirkcudbrightshire, and no doubt did formerly in the Counties of

Forfar, Stirling, Moray, and Sutherland. In Wales also, at Glodclaeth.

Mountains as well as level districts are frequented by the Goshawk,

but in either case it seems to prefer a variety of woodland and open

country, and not to be partial either to the dense monotony of a forest,

or the dangerous exposure of an open unsheltered plain. Mudie says

that it also dwells in the rocky cliffs of the sea coast, but he gives

no authorities for, or instances of this being the case.

In general habits this species is considered to resemble the Sparrow-Hawk.

At night it roosts in coppice wood in preference to lofty trees, and

the lower parts of such instead of the top, rarely on rocks in the

more open parts of the country. 'When at rest,' says Meyer, 'he sits

in a slouching attitude, with his back raised, and his head rather

depressed, but does not drop his tail in the manner that some other

birds of prey are in the habit of doing.' The Goshawk will at times

attack the Eagle. The male is said to be a much more spirited bird

than the female, and to have been on this account the rather valued

in the gay science, though its training was more difficult than that

of some other species. Great havoc is committed in preserves when

the young ones are expecting food in the nest. At other seasons of

the year the more open country may be traversed for its own supply

by the Goshawk. Montagu was informed by Colonel Thornton that, at

Thornville Royal, in Yorkshire, one was flown at a pheasant, and must

have kept by it all night, for both were risen together by the falconer

the next morning. Like several others, perhaps all of the Hawk kind,

the one before us is the object of the persevering and unaccountable

attacks of the Rooks. Who that has lived in the country has not seen

this, and observed it even from childhood ? Yet there are those, whose

lot has unfortunately been cast in towns, who have never seen even

so common a sight as this. I well remember when travelling some years

ago on a stage coach over the Dorsetshire Downs, a lady who was going

down into Devonshire with her son from London, seeing some gleaners

in a field, observed that they were the first she had seen that year

: 'they are the first,' said the youth, 'that I have ever seen in

my life !'

The Goshawk has great powers of flight, and its rapid and intricate

movements among trees and cover give in one sense ample scope for

their exercise and development. This bird for the most part flies

low in pursuit of its prey, which it attacks from below or sideways,

not from above like other Falcons, but occasionally it soars at a

considerable elevation, wheeling round and round with extended tail,

in slow and measured gyrations. After driving its game into a tree,

bush, or other cover, it will watch outside until it is compelled

to leave its place of refuge by hunger or fear, when of course it

is snapped up; but, if the quarry should gain an advantage at the

beginning of the chase, it is frequently relinquished altogether.

Its flight is very quick, though its wings are short, and its game

is struck in the air, if belonging to that element.

The food of the Goshawk, which is carried into its retreat in the

woods, to be devoured there without interruption, consists of hares,

rabbits, squirrels, and sometimes mice, and of pigeons, pheasants,

partridges, grouse, wild-ducks, crows, rooks, magpies, and other birds.

'According to Meyer,' says Selby, 'it will even prey upon the young

of its own species.' Living prey alone is sought, and before being

devoured it is plucked carefully of the fur or feathers—very

small animals are swallowed whole, but the larger are torn in pieces,

and then swallowed: the hair or fur is cast up in pellets. Sometimes

a pigeon is heedlessly followed into a farmyard, and sometimes the

'biter is bit' in the ignoble trap, in the act of attempting, like

the Kestrel, to carry off the decoy birds of the fowler. Its appetite,

though it is a shy bird, leads it into these difficulties, and so,

again, when replete with food, and enjoying, it may be, a quiet 'siesta,'

the sportsman steals a march, and down falls the noble Goshawk. Yarrell

says that in following its prey, 'if it does not catch the object,

it soon gives up the pursuit, and perching on a bough waits till some

new game presents itself,' It will kill a rabbit at a single blow.

'Its mode of hunting,' says Bishop Stanley, 'was to beat a field,

and when a covey was sprung to fly after them, aud observe where they

settled; for as it was not a fast flyer, the Partridges could outstrip

it in speed: it then sprung the covey again, and after a few times

the Partridges became so wearied that the Hawk generally succeeded

in securing as many as it pleased. To catch it a trap or two was set

in its regular beat, baited with a small rabbit, or the stuffed skin

of one; but a surer mode, particularly in open unenclosed countries,

was by preparing what were called bird-bushes, about half a mile from

each other. A large stake was driven into the ground and left standing,

about seven feet in height; bushes and boughs were then laid round

this post and kept loosely open, and hollow at the bottom, to the

extent of ten or twelve yards round the post, for the Partridges to

run into when pursued by the Goshawk, which they usually did after

being disturbed two or three times. The Goshawk finding itself disappointed,

and unable to follow them with its long wings amongst the bushes and

briers, after flying round them for some turns, was sure to perch

upon the top of the post, as the only resting place at hand, and was

as sure to be taken by a trap set there for the purpose.' Mr. P. H.

Salvin of Whitmoor House, near Guildford, has written to me of one

of his birds which killed in one day in 1881, one hare of nine pounds

and a half weight, thirteen rabbits, and a squirrel.

'His voice in times of danger,' says Meyer, 'is a loud single note,

many times repeated, and bears a great resemblance to that of the

Sparrow-Hawk; besides this cry, he utters another much resembling

the note of the Peregrine-Falcon, which is chiefly used when engaged

in a contest with some other bird of prey.'

Its nest is said to be built in tall fir or other trees, near the

trunk, and to be large in size, flat in shape, and composed of sticks,

grass, and moss, loosely put together. The bird is believed to be

in the habit frequently of occupying it for several years in succession,

making the necessary repairs from time to time. Mr. Hewitson says

that it 'is placed in some high tree in the interior of the woodland,

except in those parts which are cleared, and free from timber.' Daring

the time that the female is sitting she is fed by the male.

The eggs are from two to five in number, greenish or bluish white,

often with and sometimes without, or nearly without, streaks and small

spots of brown, olive, or reddish, or yellowish brown. They are hatched

about the middle of May, after an incubation of about three weeks.

Mr. Gurney had one of these birds which laid eggs several times, and

seemed disposed to sit on them.

The Goshawk is very strong and robust in make. Male; length, from

one foot six to one foot nine inches; bill, light blue at the base,

bluish black towards the end, and bristled on the sides; cere, yellow;

iris, bright yellow in the fully adult bird; over the eye is a broad

white line spotted with black; head, flat, dark brownish black on

the crown; neck, bluish grey, behind, the base of the feathers white,

dull white in front; nape, white at the under end of the feathers,

which are tipped with brownish black. Chin and throat, white, streaked

with dusky; breast, greyish white, transversely waved with small bars

of greyish black: each feather has several bars; the shafts of the

same colour; back, dark bluish grey tinged with brown; there is an

evanescent bloom of ash-colour on the living bird, which fades away

shortly after it is dead.

Wings, rather short; expanse about three feet seven inches; greater

and lesser wing coverts, bluish grey; primaries, brown, barred with

a darker shade, except towards the tips, which are dark brown; the

shafts reddish, the inner margins whitish, especially towards the

base; underneath, greyish white, the dark bars shewing through; secondaries

and tertiaries, bluish grey; greater and lesser under wing coverts,

barred with dusky transverse lines. The tail, which is long, wide,

and rounded at the end, is brownish grey, with four, five, or six,

broad bands of blackish brown, the final band the widest, the tip

white, the shafts yellowish brown, the base white; upper tail coverts,

bluish grey; under tail coverts, white, with a few slight dark markings.

The legs, which are yellow, of moderate length, and feathered rather

more than a third down, are reticulated on the sides and behind and

before with large scales or plates: the feathers on the legs are shafted

and marked as the breast, but the bars are narrower; toes, strong

and yellow, the third and fourth united by a web which extends as

far as the second joint of each; the first and second are nearly equal

in size, the fourth longer and more slender, the third much longer;

the sole of the foot is prominently embossed; claws, black, strong,

and very sharp.

The female is much larger than the male, but closely resembles him

in colour, the plumage only on the back being of a browner tint. When

very old there is hardly any apparent difference between them. Length,

from one foot ten to two feet two inches; bill, horn-colour or bluish

black; breast, greyish white, with small black bars, but tinged with

rust-colour; back, dark brown. The wings expand to about three feet

nine inches; the bars on the tail are of a dark brown.

The young birds are at first covered with white or buff-coloured down.

Bill, dark brown, paler at the base; cere, greenish yellow; iris,

grey, pale yellow, reddish or yellowish orange, according to age:

there is a white band over the eye, speckled with brown; head, reddish

brown, the centre of each feather broadly streaked with dark brown,

and edged with light yellowish red; crown, dark reddish brown, the

feathers edged with dull white or rufous; neck, behind, yellowish

or reddish white, or light brown streaked with dark brown. Nape, light

reddish brown, with an oblong dusky mark on the centre of each feather;

throat, white or cream white, speckled with brown; breast, reddish

or yellowish white, streaked longitudinally with brown on the centres

of the feathers, the shafts still darker, narrowing towards the tip

of each, until after the second moult: when the transverse bars appear,

they are at first fewer in number and larger than in after years;

back, reddish or yellowish brown, the feathers edged with a paler

shade, or yellowish white; primaries, dusky, with dark brown, and

tipped with whitish; secondaries and tertiaries, dusky, with greyish

brown bars; greater and lesser under wing coverts, light brown, or

rufous white, streaked as the feathers on the breast; tail, greyish

brown, with four or five bars of blackish brown alternating with the

former colour, and tipped with white; underneath, greyish white, barred

with five bars of greyish brown; tail coverts, yellowish brown with

paler tips; under tail coverts, yellowish white, but only marked with

brown at the tips. Legs and toes, dull yellow, inclining to green

at the joints: the feathers on the legs are light brown or rufous

white, streaked, but only on the shafts, as the feathers on the breast;

claws, brownish black, those of the inner toes larger than those of

the outer.

The young female is lighter coloured than the young male, and the

dark markings on the breast are larger. It is some years before the

fine grey of the back and the bluish white of the breast are assumed.

White varieties of this species have been sometimes met with, and

some of a tawny colour with a few brown markings.

'I have compared,' says Macgillivray, 'British and French with American

specimens, both in the adult and young states, and am perfectly persuaded

that no real difference exists between them. Were we to form specific

distinctions upon such trifling discrepancies as are exhibited by

the Goshawk of America and that of Europe, we might find that our

common ptarmigan, our bullfinch, wheatear, and kestrel, are each of

two or three species. Cuvier, in my opinion, very strangely refers

to the 'Falco atricapillus' of Wilson, which is the American Goshawk,

as a species of 'Hierofalco,' that is, as intimately allied to the

Jer-Falcon. The only name by which this species is known in Britain

is that prefixed to this article, but variously written—Goshawk,

Goss-hawk, or Gose-hawk, and apparently a corruption of Goose Hawk,'

"Then rose the cry of females shrill, As Goshawks whistle on

the hill."

The Lady of the Lake.