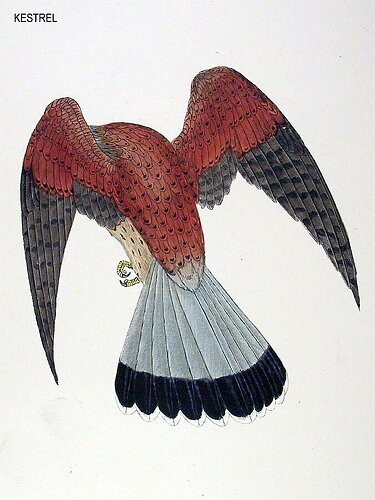

KESTREL,

WINDHOVER. STONEGALL. STANNEL HAWK. CUDYLL COCH, CEINLLEF GOCH, IN

ANCIENT BRITISH.

Falco tinnunculus, MONTAGU. SELBY. Accipiter alaudarius, BRISSON.

Falco—To cut with a bill or hook.

Tinnunculus, Conjectured from Tinnio—To chirp. (From the peculiar

note of the bird.)

This species is in my opinion, not only, as it is usually

described to be, one of the commonest, but the commonest of the British

species of Hawks. It is found in all parts of Europe—Denmark,

France, Italy, Spain, Norway, Sweden, Lapland, Finland, the Ferroo

Islands, Greece, and Switzerland; and also in Asia, in Arabia, Persia,

Palestine, Bokhara, China, and Siberia; in Northern, Western, and

Central Africa, Abyssinia, Soudan, Senegambia, Morocco, Algeria, Tripoli,

and at the Cape of Good Hope; also in Ceylon and the Seychelles on

the one side, and in the Cape de Verd Islands, the Azores, the Canary

Islands, and Madeira on the other; so too, according to Meyer, in

America. It is easily reclaimed, and was taught to capture larks,

snipes, and young partridges. It becomes very familiar when tamed,

and will live on terms of perfect amity with other small birds, its

companions. One of its kind formed, and perhaps still forms, one of

the so-called 'Happy Family,' to be seen, or which was lately to be

seen, in London. The Kestrel has frequently been taken by its pursuing

small birds into a room or building. It does infinitely more good

than harm, if indeed it does any harm at all, and its stolid destruction

by gamekeepers and others is much to be lamented, and should be deprecated

by all who are able to interfere for the preservation of a bird which

is an ornament to the country.

These birds appear to be of a pugnacious disposition. J. W. G. Spicer,

Esq., of Esher Place, Surrey, writing in the 'Zoologist,' pages 654-5,

says, 'all of a sudden, from two trees near me, and about fifty yards

apart, two Hawks rushed simultaneously at each other, and began fighting

most furiously, screaming and tumbling over and over in the air. I

fired and shot them both, and they were so firmly grappled together

by their talons, that I could hardly separate them, though dead. They

were both hen Kestrels.

What could have been the sudden cause of their rage? It was autumn,

and therefore they had no nests.' In the next article, the following

is recorded by Mr. W. Peachey, of Northchapel, near Petworth, 'a few

weeks ago, a man passing a tree, heard a screaming from a nest at

the top. Having climbed the tree and put his hand into the nest, he

seized a bird which proved to be a Kestrel; and at the same instant

a Magpie flew out on the other side. The Kestrel, it appears, had

the advantage in being uppermost, and would probably have vanquished

his adversary, had he not been thus unexpectedly taken.' Two instances

are related by the late Frederick Holme, Esq., of Corpus Christi College,

Oxford, the one of a male Kestrel having eaten the body of its partner,

which had been shot, and hung in the branch of a tree—'a piece

of conjugal cannibalism somewhat at variance with the proverb that

'hawks don't poke out hawks' een;' and the other, as a set off, he

says, of 'six of one and half-a-dozen of the other,' a pair of Kestrels

in confinement having been left without their supper, the male was

killed and eaten by the female before morning.'

In Yorkshire, the Kestrel is a common bird, as in most parts of England.

In Cornwall it appears to be rare. One, a male, was shot, Mr. Cocks

has informed me, at Trevissom, in January, 1850, by Master Reed; and

others at Penzance and Swanpool, in 1846. In Scotland it is likewise

generally distributed. In Ireland it is also common throughout the

island.

The debateable point respecting the natural history of the Kestrel,

is whether it is migratory or not. Much has been written on both sides

of this 'vexata quaestio;' and as much, or more, one may take upon

oneself to say, will yet be written on the subject. My own opinion

is against the idea of any migration of the bird beyond the bounds

of this country. Stress has been laid, in an argument in favour of

such a supposed movement, on the fact of the departure of the broods

of young Kestrels from the scene of their birth. But who could expect

them to remain in any one confined locality? Brood upon brood would

thus acumulate, in even more than what Mr. Thornhill in the 'Vicar

of Wakefield,' calls a 'reciprocal duplicate ratio;' a 'concatenation

of self-existences' which would doubtless soon find a lack of the

means of subsistence in a neighbourhood calculated probably to afford

sufficient food for only a few pairs. Unless in the case of the Osprey,

which must be admitted from the nature of its prey brought together

in vast profusion at the same period of time, to be an exceptional

one, I am not aware of any Hawks which build in company in the same

way that Rooks do: I have never yet heard of a Kestrelry. The fact

of the dispersion of the young birds is nothing more than might, from

the nature of their habit of life, be looked for. Their very parents

may expel them, as is the case with other birds of the same tribe.

They have come together from roaming over the face of the country,

to some situation suitable for them to build in, and a like dispersion

of their offspring is the natural course of things. As to any total,

or almost total disappearance of the species in winter, it is most

certainly not the general fact, whatever may appear to be the case

in any particular locality or localities. The only one I ever shot,

the brightest-coloured specimen, by the way, I ever saw, was in the

depth of winter, and it fell, on the same day as did the Merlin which

I have spoken of as having had the misfortune to come across my path,

upon snow-covered ground, with its beautiful wings stretched out,

for the last time poor bird. In the parts of Yorkshire in which I

have lived, the county with reference to which the observations I

have alluded to have been made, and I have lived in all three Ridings,

though my assertion at present applies to the East only, I have never

observed any diminution in the number of Kestrels that are seen in

the winter, from those which are to be seen in summer hovering over

the open fields. It would seem very possible, from the different observations

that have been made, that they may make some partial migrations in

quest of a better supply of food, or for some other reason known only

to themselves.

Still after what I have said, I must not be understood as unhesitatingly

asserting that none of our British born and bred Kestrels cross the

sea to foreign parts. It would be presumptuous in any one to hazard

such an assertion: in this, as in most other supposed matters of fact,

our ignorance leaves but too abundant room for difference of opinion.

'There be three things,' says Solomon, 'which are too wonderful for

me, yea, four which I know not;' and one of these he declares to be

'the way of an Eagle in the air.' We need not be ashamed of keeping

company with him in a candid confession of our own short-sightedness.

Since writing the above, I find that Mr. Macgillivray remarks that

in the districts bordering on the Frith of Forth, these birds are

more numerous in the winter than in the summer, and he adds that probably

'like the Merlin, this species merely migrates from the interior to

the coast.' And 'in the north of Ireland, generally,' says Mr. Thompson,

'Kestrels seem to be quite as numerous in winter as in summer, in

their usual haunts.'

The Kestrel begins to feed at a very early hour of the morning. It

has been known to do so even almost before it was light. Several others

of this family, as I have before had occasion to observe, continue

the pursuit of their prey until a correspondingly late hour in the

evening.

Other species of Hawk may be seen hovering in a fixed position in

the air, for a brief space, the Common Buzzard for instance, but most

certainly the action, as performed by the Kestrel, is both peculiar

to and characteristic of itself alone, in this kingdom at least. No

one who has lived in the country can have failed to have often seen

it suspended in the air, fixed, as it were, to one spot, supported

by its out-spread tail, and by a quivering play of the wings, more

or less perceptible.

It has been asserted that the Kestrel never hovers at a greater height

from the ground than forty feet, but this is altogether a mistake.

The very last specimen that I have seen thus poised, which was about

a fortnight since, in Worcestershire, seemed to me as near as I could

calculate its altitude, to be at an elevation of a hundred yards from

the ground. I mean, of course, at its first balancing itself, for

down, as the species is so often seen to do, it presently stooped,

and then halted again, like Mahomet's coffin, between sky and earth,

then downwards again it settled, and then yet once again, and then

glided off—the prey it had aimed at having probably gone under

cover of some sort: otherwise it would have dropped at last like a

stone upon it, if an animal very probably fascinated, aud borne it

off immediately for its meal. It is a bird of considerable powers

of flight. Tame Kestrels, kept by Mr. John Atkinson, of Leeds, having

had their wings cut to prevent their escape, exhibited, he says, great

adroitness in climbing trees.

The food of the Kestrel consists of the smaller animals, such as field

mice, and the larger insects, such, namely, as grasshoppers, beetles,

and caterpillars: occasionally it will seize and destroy a wounded

partridge, but when seen hovering over the fields in the peculiar

and elegant manner, so well illustrated by my friend the Rev. R. P.

Alington in the engraving which is the accompaniment of this description,

and from which the bird derives one of its vernacular names, it is,

for the most part, about to drop upon an insect. Small birds, such

as sparrows, larks, chaffinches, blackbirds, linnets, and goldfinches,

frequently form part of its food, but one in confinement, while it

would eat any of these, invariably refused thrushes; one, however,

has been seen, after a severe struggle to carry off a mistletoe thrush.

The larvse of water insects have also been known to have been fed

on by them, and in one instance a leveret, or young rabbit, and in

another a rat. Slow-worms, frogs, and lizards are often articles of

their food, as also earth-worms, and A. E. Knox, Esq. possesses one

shot in Sussex in the act of killing a large adder. Thirteen whole

lizards have been found in the body of one. Another has been seen

devouring a crab, and another, a tame one, the result doubtless of

its education, as man has been defined to be 'a cooking animal,' a

hot roasted pigeon. 'De gustibus non disputandum.'

'The Kestre,' says the late Bishop Stanley, 'has been known to dart

upon a weasel, an animal nearly its equal in size and weight, and

actually mount aloft with it. As in the case of the Eagle, it suffered

for its temerity, for it had not proceeded far when both were observed

to fall from a considerable height. The weasel ran off unhurt, but

the Kestrel was found to have been killed by a bite in the throat.''

He adds also, 'Not long ago some boys observed a Hawk flying after

a Jay, which on reaching, it immediately attacked, and both fell on

a stubble field, where the contest appeared to be carried on; the

boys hastened up, but too late to save the poor Jay, which was at

the last gasp; in the agonies of death, however, it had contrived

to infix and entangle its claws so firmly in the Hawk's feathers,

that the latter unable to escape, was carried off by the boys, who

brought it home, when on examination it proved to be a Kestrel.' The

Windhover has often been known to pounce on the decoy-birds of bird-catchers,

and has in his turn been therefore entrapped by them, in prevention

of future losses of the same kind. It has also been seen to seize

and devour cockchaffers while on the wing. When the female is sitting

the male brings her food; she hears his shrill call to her on his

return, flies out to meet him, and receives the prey from him in the

air.

It is a curious fact that notwithstanding their preying on small birds,

the latter will sometimes remain in the trees in which they are, without

any sign of terror or alarm. They have been known to carry off young

chickens and pigeons. When feeding on insects which are of light weight,

they devour them in the air, and have been seen to take a cockchaffer

in each claw. Bewick says that the Kestrel swallows mice whole, and

ejects the hair afterwards from its mouth, in round pellets—the

habit of the other Hawks. Buffon relates that 'when it has seized

and carried off a bird, it kills it, and plucks it very neatly before

eating it. It does not take so much trouble with mice, for it swallows

the smaller whole, and tears the others to pieces. The skin is rolled

up so as to form a little pellet, which it ejects from the mouth.

On putting these pellets into hot water tosoften and unravel them,

you find the entire skin of the mouse, as if it had been flayed.'

This, however, is said by Mr. Macgillivray never to be the case, but

that the skin is always in pieces. Probably in some instances there

may be foundation for the assertion of the Count, but only as exceptions

to the general rule.

Meyer observes, which every one who has seen the bird will confirm,

as frequently, though not always the case, that 'when engaged in searching

for its food, it will suffer the very near approach of an observer

without shewing any alarm or desisting from its employment, and continue

at the elevation of a few yards from the ground, with out-spread tail,

and stationary, except the occasional tremulous flickering of its

wings; then as if suddenly losing sight of the object of its search,

it wheels about, and shifts its position, and is again presently seen

at a distance, suspended and hovering in the same anxious search/

In the ardour of the chase, the Windhover has been known to drive

a lark into the inside of a coach as it was travelling along; and

another to brush against a person's head, in dashing at a sparrow

which was flitting in a state of bewildered entrancement in a myrtle

bush. Mr. Thompson mentions his having seen a Kestrel after a long

and close chase of a swallow through all its turns and twists, become

in its turn pursued by the same individual bird. They are often followed

and teased by several small birds together, as well as by Rooks, as

hereafter to be mentioned when treating of the latter bird.

The following curious circumstance is thus pleasingly related by the

Rev. W. Turner, of Uppingham, in the 'Zoologist,' pages 2296-7:—'In

the summer of 1847 two young Kestrels were reared from the nest, and

proved to be male and female: they were kept in a commodious domicile

built for them in an open yard, where they lived a life of luxury

and ease. This summer a young one of the same species was brought

and put into the same apartment; and, strange to say, the female Kestrel,

sensible (as we suppose) of the helpless condition of the new-comer,

immediately took it under her protection. As it was too infantine

to perch, she kept it in one corner of the cage, and for several days

seldom quitted its side; she tore in pieces the food given to her,

and assiduously fed her young charge, exhibiting as much anxiety and

alarm for its safety, as its real parent could have done. But what

struck me as very remarkable, she would not allow the male bird, with

whom she lived on the happiest terms, to come near the young one.

As the little stranger increased in strength and intelligence, her

attentions and alarm appeared gradually to subside, but she never

abandoned her charge, and its sleek and glossy appearance afforded

ample proof that it had been well cared for. The three are now as

happy as confined birds can be.'

In the same magazine the late Frederick Holme, Esq., of Corpus Christi

College, Oxford, records that a nest of this species was observed

to have been begun near that city; a trap was set, and five male birds

were caught on successive days, without the occurrence of a single

female; the last of them ' being a young bird of the year in complete

female plumage.' Again, at page 2765, the Rev. Henry R. Crewe, of

Breadsall Rectory, Derbyshire, relates the following pleasing anecdote

:— 'About four years ago, my children procured a young Kestrel,

which,, when able to fly, I persuaded them to give its liberty; it

never left the place, but became attached to them. In the spring of

the following year we missed him for nearly a week, and thought he

had been shot; but one morning I observed him soaring about with another

of his species, which proved to be a female. They paired and laid

several eggs in an old dove-cote, about a hundred yards from the Rectory;

but being disturbed that season, as I thought, by some White Owls,

the eggs were never hatched. The next spring he again brought a mate

: they again built, and reared a nest of young ones. Last year they

did the same; but some mischievous boys took the young ones when just

ready to fly. Though in every respect a wild bird as to his habits

in the fields, he comes every day to the nursery window, and when

it is opened, will come into the room and perch upon the chairs or

table, and sometimes upon the heads of the little ones, who always

save a piece of meat for him. His mate will sometimes venture to come

within a yard or two of the house, to watch for him when he comes

out of the room with his meat; she will then give chase, and try to

make him drop it, both of them squealing and chattering to our great

amusement. The male never leaves us; indeed he is so attached to the

children, that if we leave home for a time he is seldom seen; but

as soon as we return, and he hears the voices of his little friends

calling him by name, he comes flying over the fields, squealing with

joy to see them again. He is now so well known amongst the feathered

tribes of the neighbourhood, that they take no notice of him, but

will sit upon the same tree with him: even the Rooks appear quite

friendly.'

The note of the Windhover is clear, shrill, and rather loud, and is

rendered by Buffon by the words 'pli, pli, pli,' or 'pri, pri, pri.'

It is several times repeated, but is not often heard except near its

station, and that in the spring.

I am indebted to my obliging friend, the Rev. J. W. Bower, of Barmston,

in the East-Riding, for the first record that I am aware of of the

breeding of the Kestrel in confinement. The following is an extract

from his letter dated November 30th., 1849, relating the circumstance:—'A

pair of Kestrels bred this summer in my aviary. The female was reared

from a nest about four years ago, and the year after scratched a hole

in the ground, and laid six or seven eggs, but she had no mate that

year. Last winter a male Kestrel pursued a small bird so resolutely

as to dash through a window in one of the cottages here, and they

brought the bird to me. I put him into the avairy with the hen bird,

and they lived happily together all the summer, and built a nest or

scratched a hole in the ground, and she laid five eggs, sat steadily,

and brought off and reared two fine young ones.' I have also heard

from F. H. Salvin, Esq., of Whitmoor House, near Guildford, of their

having built and hatched young in the aviary of Mr. St. Quintin, of

Scampston Hall, near Malton; and also in that of S. C. Hincks, Esq.,

of Runfold Lodge, near Farnham. They had five eggs, of which he took

two, and the birds hatched the other three. Some pairs of Kestrels

seem to keep together throughout the winter. About the end of March

is the period of nidification. The young are at first fed with insects,

and with animal food as they progress towards maturity. They are hatched

the latter end of April or the beginning of May.

The nest, which is placed in rocky cliffs on the sea-coast or elsewhere,

is also, where it suits the purpose of the birds, built on trees,

in fact quite as commonly as in the former situations ; sometimes

in the holes of trees or of banks, as also occasionally on ancient

ruins, the towers of Churches, even in towns and cities, both in the

country and in London itself, and also in dove-cotes. Sometimes the

deserted nest of a Magpie, Baven, or Jackdaw, or some other of the

Crow kind is made use of. 'Few people are, indeed, aware,' says Bishop

Stanley, 'of the numbers of Hawks existing at this day in London.

On and about the dome of St. Paul's, they may be often seen, and within

a very few years, a pair, for several seasons, built their nest and

reared their brood in perfect safety between the golden dragon's wings

which formed the weathercock of Bow Church, in Cheapside. They might

be easily distinguished by the thousands who walked below, flying

in and out or circling round the summit of the spire, notwithstanding

the constant motion and creaking noise of the weathercock, as it turned

round at every change of the wind.' "When built in trees, the

nest is composed of a few sticks and twigs, put together in a slovenly

manner, and lined with a little hay, wool, or feathers : if placed

on rocks, hardly any nest is compiled—a hollow in the bare rock

or earth serving the purpose. William Thompson, Esq., mentions a curious

fact of a single female Kestrel having laid and sat on four eggs of

the natural colour, in the month of April, 1848, after having been

four years in confinement. An unusual fact occurred near Driffield

in the year 1853, four eggs having been taken out of a nest, (the

whole number in it,) five more were laid within a few days afterwards.

The eggs, which are of an elliptical form, and four or five in number,

sometimes as many as six—six young birds having been found in

one nest—are dingy white, reddish brown or yellowish brown,

more or less speckled or marbled over with darker and lighter specks

or blots of the same. Mr. Yarrell says that the fifth egg has been

known to weigh several grains less than either of those previously

deposited, and it has also less colouring matter spread over the shell

than the others; both effects probably occasioned by the temporary

constitutional exhaustion the bird has sustained. In the 'Zoologist,'

page 2596, Mr. J. B. Ellman, of Rye, writes, 'this year I received

some eggs of the Kestrel, which were rather dirty; so after blowing

them, I washed them in cold water, and much to my surprise the whole

colour came off, leaving the eggs of a dirty yellow, speckled with

drab. Not long after this I received five eggs from another Kestrel's

nest, which were exactly like those I had previously after they were

washed.'

Male; weight, about six ounces and a half; length, thirteen inches

and a half to fourteen inches and a half, or even fifteen inches;

bill, strong, and with the tooth prominent, pale blue, or bluish grey,

the tip black, and the base close to the cere tinged with yellow;

cere, pale orange, or yellow; iris, dark brown, approaching to black;

the eyelids are furnished with short bristles; forehead, yellowish

white; head, on the crown, ash grey, each feather being streaked in

the centre with a dusky line; on the sides, the same colour tinged

with yellow: there is a blackish grey mark near the angle of the mouth

pointing downwards, and a line of the same along the inner and upper

edge of the eye; neck and nape behind and on the sides, lead-colour,

faintly streaked with black, with a purplish tinge, as is the case

with the other black feathers; chin and throat, yellowish white, without

spots; breast, pale yellowish orange red, each feather streaked with

dark brown, and a spot near the end of the same; back on the upper

part, bright cinnamon red, the shafts of each feather being blackish

grey, with a spot of the same colour near the end, on the lower part

bluish grey.

My instructions to the printer were 'do not be afraid of making the

colour too bright.' Nothing can exceed the beauty of the rich cinnamon-red

colour of a well plumaged male Kestrel, so chastely bespotted with

crescent-shaped black marks.

The wings, which are rather long and broad, but narrow towards the

ends, expand to the width of two feet three inches, and reach to within

about an inch and a half from the tip of the tail; greater wing coverts,

brownish black, tinged with grey; primaries, brownish black, tinged

with grey, margined and tipped with a paler shade, and the inner webs

thickly marked with white, or reddish white; the second is the longest,

the third almost the same length, the fourth a little longer than

the first, which is nearly an inch shorter than the second; underneath,

barred with darker and paler ash-colour; secondaries, cinnamon red

on the inner side, namely, on the outer web, the inner being dusky

with reddish white markings, and on the outer side as the primaries;

greater and lesser under wing coverts, white, the latter beautifully

spotted with brown. The tail, which consists of twelve long rounded

feathers, the middle ones being an inch and a half longer than the

outer ones, is ash grey, or bluish grey; the shafts, and a bar, which

shews through near the end, of an inch in breadth, blackish brown,

or purple black, the tip, greyish white; upper tail coverts, ash grey,

or light bluish grey, as the tail. The legs, which are feathered in

front more than a third down, and covered all round with angular scales,

and the toes, bright yellow or orange: the third and fourth are connected

at the base by a very short web. Claws, black, tinged with grey at

the base.

The female differs but little in size from the male, at least in comparison

with others of the Hawks. Length, from fourteen inches and a half

to fifteen inches and a half; bill, cere, and iris, as in the male.

Head, reddish, slightly shaded with bluish grey; neck, chin, throat,

and breast, pale yellowish red streaked with dark brown—those

on the sides forming transverse bands; back, dull reddish rust-colour,

barred with dark brown, each feather having four angular bands of

brown and three of red, and tipped with the latter, the shafts dark

brown. The wings expand to the width of two feet four inches, or even

to two feet and a half; the spots are less distinct than in the male.

The second quill feather is the longest, the third nearly as long,

and a little more than half an inch longer than the first. Greater

and lesser wing coverts, darker than in the male; primaries, blackish

brown, with transverse spots of pale red, and margined with white,

the two first having their inner webs deeply notched, the second and

third with the outer web strongly hollowed; secondaries, marked as

the back. Greater and lesser under wing coverts, reddish white or

yellowish white, with oblong brown spots. The tail and upper tail

coverts, as the head, and the former barred with about ten narrow

bars of blackish brown, the end one nearly an inch in breadth, the

tip reddish white. The under surface is more uniform in colour, and

less distinctly barred than in the male. Under tail coverts, unspotted.

The feathers on the legs streaked with small dark markings.

The young are at first covered with white down, tinged with light

sand-colour; iris, bluish black: when fully fledged, the bill is light

bluish grey, tipped with yellowish grey or horn-colour; cere, pale

greenish blue; iris, dusky, tinged with grey. Head, light brownish

red, streaked with blackish brown. At the first moult the bluish grey

appears mixed with the red in the male, and becomes more pure as the

bird advances in age. Neck, on the sides pale yellowish red streaked

with dark brown; nape, as the head; chin, throat, and breast, pale

yellowish red streaked with dark brown. Back, light red, but of a

deeper shade than in the old birds—each feather crossed with

dark brown bands. Greater and lesser wing coverts, dark brown, tipped

and spotted with red; primaries, reddish brown, tipped with light

red, and spotted with the same on the inner webs; secondaries, spotted

on the outer webs and barred on the inner with red. The tail, light

red, barred on the inner webs with eight bands of brown, the end one

being three-quarters of an inch in width; the tip dull reddish white;

underneath, it is light reddish yellow. At the first moult the bluish

grey tint appears in the male and the bars on both webs. The legs

and toes, light yellow; the feathers, light reddish yellow—some

of them with a dusky line in the centre. Claws, brownish back, the

tips being paler.

The dark marks become smaller as the bird advances in age: those on

the outer webs of the tail wear off first: those on the inner webs

continue for two years. The female alters but little, assuming in

a faint degree the greyish blue tint on those feathers which are of

that colour in the male—the tail always remains barred.

The young are at first covered with yellowish white down.

"And with what wing the Stannyel checks at it."

Twelfth Night.