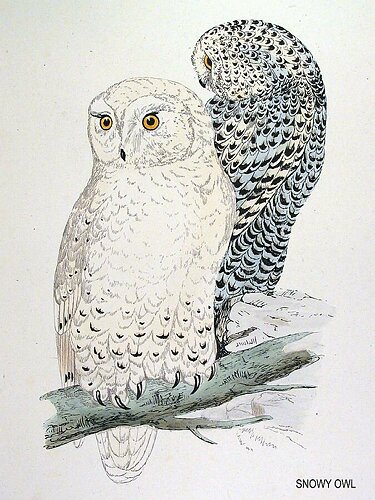

SNOWY OWL.

Strix nyctea, MONTAGU. BEWICK. Sturnia nyctea, SELBY. GOULD. Noctua

nyctea, JENYNS,

Strix—Some species of Owl. Nyctea—An adjective from Nix—Snow.

The Snowy Owl may derive its name either from the snow-white

colour of its plumage when fully adult, or from the snow-covered regions

which are its natural residence.

It inhabits the Arctic parts of Europe, Asia, and America; from these

it sometimes advances more or less far towards the south as to Texas,

but the farther the seldomer. In Europe it occurs in abundance in

Kamtschatka, and in considerable numbers in Russia, Lapland, Norway,

and Sweden, as also in Spitsbergen, the Ferroe Islands, Iceland, and

Greenland, occasionally in Prussia, Pomerania, Silesia, Austria, Poland,

Germany, France, and Switzerland, and once appeared in Holland, in

the winter of 1802, once in Bermuda, October 15th., 1847, and is said

to have been previously abundant there. In Asia it is met with, in

Siberia.

This splendid Owl has been one of the 'oldest inhabitants' of the

Orkney and Shetland Islands, and specimens have been procured there,

but like that well-known character it is now fast becoming apocryphal:

beauty in Owls, as well as in human beings, is a dangerous possession,

and often entails damage and destruction. It has occurred likewise

in the Hebrides, in Mull, Iona, and Skye. One was killed on the Isle

of Unst, in the month of August or September, 1812, another was observed

at Ronaldshay the same year: old birds and young together have been

regularly seen in that island, and also on Yell, in which they were

said to have been accustomed to breed. One in Orkney, which had been

driven there in a storm from the north-west, at the end of March,

in 1835. In Yorkshire a specimen was shot on Barlow Moor, near Selby,

on the 13th. of February, 1837, and another was seen in company with

it at the same time. One was shot at Elsdon, in Northumberland, in

December, 1822, and two near Rothbury, in the same county, at the

end of January, 1823, during a severe snowstorm; another was seen

about Scarborough in the same storm, at the end of 1879; one in Norfolk

in 1814, and one in 1820; a third at Beeston, near Cromer, on the

22nd. of January, and a fourth at St. Faiths, about the end of February,

1850. A fifth had been seen at Swannington, the middle of the preceding

year; one was killed at Frinsted, in Kent, in 1844; one at Langton,

near Blandford, in Dorsetshire: and one, as I am informed by Mr. R.

A. Julian, Junior, was knocked down with a stick by a boatman, on

the bank of the river Tamar, near St.Germains, in Cornwall, in December,

1838; another was found dead near Devonport, in Devonshire, in the

same year, in which, it may be remarked, a flock was seen to accompany

a ship half way across the Atlantic.

One at St. Andrews, in Suffolk, on the 19th. of February, 1847. It

was shot from the stump of a pollard elm, whence it had been seen

to dart down into the field, and then to return to its perch.' ' It

had previously been seen, for there is no reasonable doubt but that

it was the same bird, at Brooke, in the county of Norfolk. One was

seen near Melbourne, in Derbyshire, on the 20th. of May, 1841. Near

Caithness a specimen was obtained in January, 1850, in stormy, snowy

weather. It was shot with a duck in its talons, which it had carried

off from a sportsman by whom the latter had just been killed, and

who had previously fired without success to endeavour to make it drop

the quarry. This appears to be a usual habit with it. In Sutherlandshire,

these birds are not very unfrequently driven on the north and north-east

coasts, after gales from that quarter.

In Ireland, specimens have occurred in the years 1812 and 1827: also

in 1835, about the 20th. of March, one was shot near Portglenone,

in the county of Antrim; on the 21st. another was seen in the same

neighbourhood. One was shot in the county of Mayo, also in the month

of March, a second in 1859, and a third in 1859; one in the month

of April in the county of Longford, where another had been procured

about the year 1835; one on the 2nd. of December, 1837, on the Scrabo

Mountain, in Downshire, and one near Killibegs, in the county of Donegal,

in November or December, 1837. One in Bevis Mountain, near Belfast,

in November, 1862; another had been obtained near that town a few

years previously; one was shot January 26th., 1856, at Summer Hill,

Killala, County Mayo, by Thomas Palmer, Esq., of that place, whose

son saw another near there in November, 1860; one near Omagh, in the

county of Tyrone, in the year 1835; two were seen by Professor Kinahan,

who has sent me an account of several of these instances, in Tipperary,

in December, in 1853; one again near Swords, in the county of Dublin,

at the end of 1862; also in Armagh.

Large flights of these birds were observed off the coast of Labrador,

in the month of November, 1838, on their migration. They accompanied

the ship for fourteen days, and frequently alighted on the yards.

Four were captured and brought to Belfast by the captain. They have

been similarly observed in two different years on the coast of Newfoundland,

each time in the month of September.

They hunt their prey by day, occasionally all day long, and even in

the brightest sunshine, on which account I cannot think that their

being seen sometimes perched under the shelter of projecting stones,

can be, as some have thought, for the purpose of avoiding a strong

glare of light: they seem to have no dread of a 'coup de soleil.'

Though the frozen regions are the home of these birds, they appear

to be able to bear heat without inconvenience. They are of a shy nature,

but will sometimes approach a sportsman, in anticipation of his furnishing

them with food, and are not deterred even by the sound of the gun,

but rather seem to consider it as a dinner bell, whose summons calls

them to a meal. They frequent open snow-covered districts, and also

mountains and wooded ones, and perch upon a stone or other eminence,

from whence they can keep a look out. Their similarity of colour to

the snow may possibly give them some advantage, as the rifle green

to the rifle brigade, at least so it has been suggested. If put up,

they fly a little way, and then, generally, 'light again. They are

said, when fat, to be good eating. When they begin to prowl about,

they are followed, like the Hawks, by Rooks and other birds. Instances

are reported to have occurred when they have been surprised asleep,

and caught napping. When taken young they may be partially tamed;

one kept by Mr. Edward Fountaine laid one egg in 1870, and in 1871,

four.

In flight these birds are very active, resembling in this respect

the Hawks more than the Owls, though the airy lightness of the latter

on the wing is by no means lost. Mr. Thompson, of Belfast, has well

remarked that rare birds which are met with wandering about the country,

are, for the most part, young ones, and the reason doubtless is that

touched upon by me in treating of the Kestrel—the parent birds

retain possession of their own native haunts—the young are compelled

to rove.

The food of this species consists of hares, rabbits, rats, lemmings,

squirrels, and other animals, as also of capercaillie, ptarmigan,

ducks, partridges, sandpipers, and any others of the smaller birds.

Mr. Mudie's theory is that the hares and ptarmigan would be destroyed

by famine and cold in the winter if they were not devoured by the

Snowy Owls, so that it would appear that they have to feel indebted

to the latter for putting them out of the way of future misery. They

prowl for prey near the ground, and strike with their feet. They are

said in case of necessity to feed on carrion. Small prey, such as

young rabbits, and small birds, they, occasionally at all events,

swallow whole, the fur being cast up in pellets. They also feed on

fish, which they dexterously skim from the surface of the water, or

sometimes, like other fishermen, watch for from the brink of a stream.

Their mode, however, of angling, is in this case, as described by

Audubon, a very peculiar one: they approach the brink of a rock, lay

down flat upon it close to the water, and when a fish comes within

reach, strike at it with their talons, and secure it with this natural

kind of gaff.

The note is said sometimes to resemble the cry of a person in danger,

but ordinarily is more like that of the Cuckoo, though shorter and

quicker. They also hiss and fuff like a cat, and make a snapping noise

with their bills, and sometimes croak like a frog.

The nest is made on the ground on a hummock, or upon rocks, though

sometimes it is said, in trees, and is then composed of branches lined

with a little moss or a few feathers.

The eggs are white, but by Veilliot said to be spotted with black,

and two, three, or four, or, it is said, six to eight, or even more

in number, of which only two are thought to be in general hatched.

Since this account however, Mr. H. W. Fielden, of the Polar expedition,

found them to be seven. It is stated that they are not all hatched

together, but that sometimes the first are out when the last are laid.

Male; weight about three pounds or a little over; length, from one

foot ten or eleven inches to two feet; bill, black; iris, bright yellow;

bristled white feathers nearly hide the bill. The ruff round the head

is scarcely apparent; it and the crown, neck, nape, chin, throat,

breast, and back, are white in the fully adult bird, with only a few

dark spots, if any, about the head, but spotted in less mature specimens

as in the female, but the spots are not so dark. When feeding, the

bird sets up a little tuft of feathers on each side of the head, so

as to resemble small horns. The wings extend to rather more than two-thirds

the length of the tail, and expand to about four feet nine inches;

greater and lesser wing coverts, white. Primaries also white: the

first is sometimes longer than the fifth, but often shorter; the second

and fourth are nearly equal, and a little shorter than the third,

which is the longest. Secondaries, tertiaries, larger and lesser under

wing coverts, all white; tail, wedge-shaped; tail coverts, white.

Legs, rough and completely covered with long hairy feathers, which

almost conceal the claws: the toes are also covered by the plumage.

Claws, black, very long, and much curved, the inner and middle ones

much grooved, the others round.

The female does not often attain to the perfectly white plumage; the

spots are at the end of each feather, and of a crescent shape on the

breast, and more elongated on the back. Weight, above three pounds;

length, from two feet one or two to two feet three inches; bill, black;

iris, bright yellow; bristles over the bill. Head, on the crown thickly

studded with round black spots; neck and nape, spotted with dark brown;

chin, throat, and breast, white, spotted more or less with brown,

and the sides somewhat barred; back, spotted with dark brown. The

wings expand to the width of five feet two inches ; greater and lesser

wing coverts, spotted with dark brown; primaries, white, barred with

dark brown bars, two inches apart; secondaries and tertiaries, white,

spotted with dark brown; larger and lesser under wing coverts, white,

spotted with more or less of brown. Tail, white, banded with bars

of broad brown spots; tail coverts, as the back. Legs and toes, as

in the male, but with a few spots; claws, black.

The young are at first covered with brown down, and have their first

feathers also light brown. Their next plumage is similar to that of

the female, only that they are much more spotted all over: in fact

the abundance of spots is a sign of youth, as their absence is of

age.

"Along he steals with noiseless flight, But oft his waving pinions

white Seen dimly, and sepulchral screech,

From the dark wood of oak or beech, Give to the eye and startled ear

Fancies of fearful spectres drear."

BISHOP MANT.