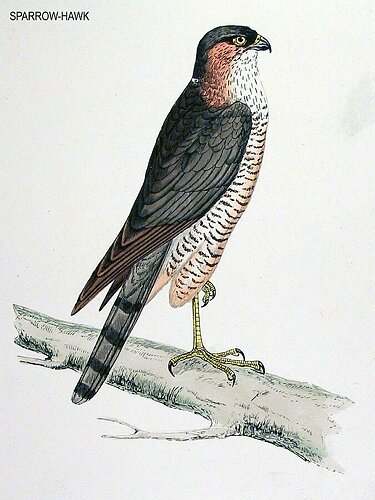

SPARROW-HAWK.

PILAN, GWEPIA, IN ANCIENT BRITISH.

Accipiter fringillarius, SHAW. SELBY. Falco nisus, LINNAEUS. LATHAM.

Buteo nisus, FLEMING.

Accipiter—Accipio—To take. Fringillarius—Fringilla—A

Finch.

'Take it for all in all,' there is perhaps no bird of

the Hawk kind more daring and spirited than the one before us—next

to the Kestrel the most common of the British species of that tribe.

It hunts in large woods, as well as in the open fields, and may frequently

be seen sweeping over hedges and ditches in every part of the country.

In the winter the males and females, like the chaffinches, appear

to separate: the motive is of course unknown.

The Sparrow-Hawk is very numerous in various parts of the world; throughout

Europe, from Russia, Denmark, Sweden, and Norway, to Spain; in Africa,

even as far as the Cape of Good Hope; in Asia, in China, Asia Minor,

Arabia, India, and Japan; but it does not occur, I believe, in America.

It is numerous also in Ireland and Scotland, and is met with likewise

in the Hebrides.

It prefers cultivated to uncultivated districts, even when the latter

abound in wood, though wooded districts are its favourite resorts.

The Rev. Leonard Jenyns says that in Cambridgeshire the males are

much less frequently seen than the females, and this observation appears

to be also general in its application, not as we may suppose from

any disparity in numbers between the two, but from the female being

of a more bold, and the male of a more shy and retiring disposition.

The organ of combativeness, according to phrenologists, would appear

to be largely developed in this bird: it seems to have universal 'letters

of marque,' and to act the part of a privateer against everything

that sails in its way—a modern specimen of 'Sir Andrew Barton,

Knight.' It will fearlessly attack in the most pugnacious manner even

the monarch of the air—the Golden Eagle, and has been known

so far to obtain the mastery, as to make him drop a grouse which he

had made a prize of: one has been seen after a first buffet, to turn

again and repeat the insult; and another dashed in the same way at

a tame Sea Eagle which belonged to R. Langtry, Esq., of Fortwilliam,

near Belfast.

The Sparrow-Hawk occasionally perches on some projection or eminence

of earth, stone, or tree, from whence it looks out for prey. If successful

in the ken, it darts suddenly off, or if otherwise, launches into

the air more leisurely. When prowling on the wing, it sweeps along,

apparently with no exertion, swiftly, but gently and stealthily, at

one moment gliding without motion of the wings, and then seeming to

acquire an impetus for itself by flapping them, every obstacle in

the way being avoided with the most certain discrimination, or surmounted

with an aerial bound: I have often thus seen them. Sometimes for a

few moments it hovers over a spot, and after flying on a hundred yards

or so, repeats the same action, almost motionless in the air. Its

flight is at times exceedingly rapid, and it was formerly employed

in the art of falconry, for hunting partridges, landrails, and quails.

It often flies late in the evening. 'During the course,' says Sir

William Jardine, 'some stone, stake, or eminence is often selected

for a temporary rest; the station is taken up with the utmost lightness—the

wings closed with a peculiar quiver of the tail, and the attitude

assumed very nearly perpendicular, when it often remains a few minutes

motionless; the flight is again resumed with as little preparatory

movement as it was suspended.' It takes its prey both in the air and

on the ground, but so great is the celerity of its flight, that a

spectator sometimes cannot tell whether it has seized it on the latter

or in the former element.

Unlike the Kestrel, which has a predilection for quadrupeds, the food

of this species consists principally of the smaller birds, and some

that are larger—snipes, larks, jays, blackbirds, swallows, sparrows,

lapwings, buntings, pigeons, partridges, landrails, thrushes, pipits,

linnets, yellow-hammers, bullfinches, finches, as also, occasionally,

mice, cock-chaffers and other beetles, grasshoppers, and even sometimes

when in captivity, its own species; small birds are devoured whole,

legs and all; the larger are plucked. Of two which I lately had in

my possession, kept in an empty greenhouse belonging to a friend,

one was found dead one morning, and partly devoured; and I have heard

of another similar instance. Whether it had died a natural or a violent

death is uncertain, but as they quarrelled over their food—they

were both females—the latter is the most probable. Mr. Selby

says that he has often known such cases. The first blow of the Sparrow-Hawk

is generally fatal, such is the determined force with which with unerring

aim it rushes at its victim; sometimes indeed it is fatal to itself.

One has been known to have been killed by dashing through the glass

of a greenhouse, in pursuit of a blackbird which had sought safety

there through the door; and another in the same way by flying against

the windows of the college of Belfast, in the chase of a small bird.

The voracity and destructiveness of this species is clearly shewn

by the fact, witnessed by A. E. Knox, Esq., of no fewer than fifteen

young pheasants, four young partridges, five chickens, two larks,

two pipits, and a bullfinch, having been found in and about the nest

of a single pair at one time. One was shot in Scotland which contained

three entire birds, a bunting, a sky lark, and a chaffinch, besides

the remains of a fourth of some other species. The young appeared

to have been catered for in the place of their birth by their parents,

even after they were able to fly to some distance from it. A pigeon

has been known to have been carried by a female Sparrow-Hawk a distance

of one hundred and fifty yards. It appears from facts communicated

to me by Mr. J. G. Fenwick, of Moorlands, near Newcastle, that it

is only the female of this and other species of Hawk that feed their

young. The male bird forages and brings the booty to the nest, but

does no more, leaving it then to his partner to divide the prey among

the nestlings; and, if she be destroyed, they then follow her in death

through want of the care which she alone, and not her partner, has

instinct to supply.

Small birds in their turn sometimes pursue and tease their adversary

in small flocks, but generally keeping at a respectful distance, either

a little above, or below, or immediately behind: their motive, however,

is at present, and will probably remain, like many other arcana of

Nature, inexplicable. A male Sparrow-Hawk which had a small bird in

its talons, has been seen pursued by a female for a quarter of an

hour through all the turns and twists by which he avoided her, and

successfully, so long as the chase was witnessed. Several instances

have been known where houses, and in one instance a Church, no regard

being had to the right of sanctuary, have been entered by this bird,

in pursuit of its prey—its own capture being generally the consequence;

and one has been seen, immediately after the discharge of a gun, to

carry off a dunlin which had been shot and had fallen upon the water,

poising himself for a moment over it in the most elegant manner so

that he might not be wetted, and then drooping his legs and clutching

it most cleverly.

Great however as is the power of flight of the Sparrow-Hawk, as evinced

in pursuit of its prey, the latter sometimes manage to rush into covert,

or crouch very close to the ground, in time to save their lives. In

one instance considerable strategy has been witnessed on both sides—a

thrush, pursued by one of these birds over the sea, made the most

strenuous efforts to gain a wood on the land, but her retreat was

each time cut off by the Hawk, until the former took refuge on the

mast of a steamer: the pirate dashed boldly after his prize, and was

with difficulty scared from seizing it there and then. Baffled for

the moment he flew himself off to the wood, but on the poor thrush

after some time, but, alas! too soon, leaving her asylum, and making

for the shore, he was observed to sally from his ambush, and secure

his reprieved victim. A lark thus harried has been known to make several

attempts to fly into the breast of a gentleman—a swallow to

find an actual refuge in that of a lady.

The author of the 'Journal of a Naturalist' confirms the idea that

their prey are sometimes fascinated by Hawks, by the following fact:

—'A beautiful male bullfinch that sat harmlessly pecking the

buds from a blackthorn by my side, when overlooking the work of a

labourer, suddenly uttered the instinctive moan of danger, but made

no attempt to escape into the bush, seemingly deprived of the power

of exertion. On looking round, a Sparrow-Hawk was observed, on motionless

wing gliding rapidly along the hedge, and passing me, rushed on its

prey with undeviating certainty.'

'In pursuit of prey,' says Bishop Stanley, 'they will not unfrequently

evince great boldness. We knew of one which darted into an upper room,

where, a goldfinch was suspended in a cage, and it must have remained

there some time, and continued its operations with great perseverance,

as on the entrance of the lady to whom the poor bird belonged, it

was found dead and bleeding at the bottom, and its feathers plentifully

scattered about." See, however, the effect—the good effect—of

education. 'Even the Sparrow-Hawk,' says the same kind-hearted writer,

'which by some has been considered of so savage and wild a nature

as to render all means for taming it hopeless, has, nevertheless,

in the hands of more able or more patient guardians, proved not only

docile, but amiable in its disposition. About four, years ago, a young

Sparrow-Hawk was procured and brought up by a person who was fond

of rearing a particular breed of pigeons, which he greatly prized

on account of their rarity. By good management and kindness he so

far overcame the natural disposition of this Hawk, that in time it

formed a friendship with the pigeons, and associated with them. At

first the pigeons were rather shy of meeting their natural enemy on

such an occasion, but they soon became familiarized, and approached

without fear. It was curious to observe the playfulness of the Hawk,

and his perfect good humour during the feeding time; for he received

his portion without any of that ferocity with which birds of prey

usually take their food, and merely uttered a cry of lamentation when

disappointed of his morsel. When the feast was over, he would attend

the pigeons in their flight round and round the house and gardens,

and perch with them on the chimney-top or roof of the house; and this

voyage he never failed to take early every morning, when the pigeons

took their exercise. At night he retired and roosted with them in

the dove-cote, and though for some days after his first appearance

he had it all to himself, the pigeons not liking such an intruder,

they shortly became good friends, and he was never known to touch

even a young one, unfledged, helpless, and tempting as they must have

been. He seemed quite unhappy at any separation from them, and when

purposely confined in another abode he constantly uttered most melancholy

cries, which were changed to tones of joy and satisfaction on the

appearance of any person with whom he was familiar. The narrator of

the above concludes his account by adding, that he was as playful

as a kitten and as loving as a dove." Meyer records an instance

near Weybridge, of a pair of wood-pigeons building their nest and

rearing their young in a cedar tree, which was at the same time the

'locale' of a pair of Sparrow-Hawks.

Before the nest is begun to be built, and while it is building, the

birds may be seen soaring, though not very high, over the eyrie, and

darting and diving about. When first the female begins to sit, she

is shy, but becomes by degrees more assiduous in her task. The male

does not watch, nor does either bird display the emotions evinced

by the true Falcons in the care of their nest. When the young are

hatched, rather more anxiety is depicted, and much courage shewn,

at least in the case of the female, the male flying off from an enemy;

and one instance is recorded of a female dashing at an intruder and

knocking off his cap. A male has been known to feed the young for

eight days after his partner had been captured, and, as it would seem,

by dropping the food to them from the air, so as to avoid the trap

himself: all the birds thus brought to them were plucked, and had

the heads taken off. Meyer says that the Sparrow-Hawk hides himself

behind a bush to devour his prey, being very jealous of observation:

he sometimes pounces on the decoy birds of the fowler.

Nidification commences in April.

The nest, which has frequently been the previous tenement of a crow,

magpie, or other bird, but most commonly repaired by itself, is built

in fir or other trees, or even bushes of but moderate height, as also

in the crevices of, or on ledges of rocks, and old ruins. It is large

in size, flat in shape, and composed of twigs, sometimes with, but

often without a little lining of feathers, hair, or grass. This species

seems, however, to be only seldom its own architect in the first instance,

but the same nest is sometimes resorted to from year to year; in fact,

it is the opinion of Mr. Hewitson, no mean one, that the Falcons very

rarely make a nest for themselves; an action of ejectment is commenced

in person against some other tenant at its own will of its own property

—no notice to quit having previously been given—and, notwithstanding

this legal defect, forcible possession proves to be nine points of

the law,, and 'contumely' is all the satisfaction that 'patient merit

of the unworthy takes.'

The eggs are of a rotund form, white or pale bluish white in colour,

much blotted, particularly at the base, with very deep reddish brown,

or crimson brown, and from three to five or six, or even seven, in

number. They vary, however, very frequently in their markings, which

in some instances are obscure and indistinct, and in others, the dark

blots are at the smaller instead of the larger end. In some the above

colouring is spread over the whole surface. The young are hatched

after an incubation of three weeks.

In no species of Hawk is the disparity in the size of the sexes more

conspicuous than in the one at present before us. Male; weight, from

five to six ounces; length, from eleven inches and a half to one foot

one inch. Bill, light blue at the base, bluish black at the end; cere,

greenish yellowish; iris, bright yellow: it is protected above by

a strong bony projection, on which the feathers are partly, white;

bristles from the base of the bill overhang the nostrils. The feathers

on the back of the head are white at the base, and seen more or less

as they are raised, giving that part an indistinct mark. The forehead

and sides of the head are yellowish red. Neck, pale reddish in front,

the shafts dark; chin and throat, very pale or rusty or yellowish

red; each feather has five bands of white, and six of pale red and

dusky—shafts partly dark. Breast, rusty red, waved in bands—the

shafts with two or three dark marks on the upper part, but without

on the lower; back, deep greyish blue, the shafts darker: an evanescent

bloom pervades this colour in the bird, which fades away more or less

quickly after its death. The wings are of moderate length, reaching

beyond the middle of the tail, and expanding to the width of one foot

eleven inches; in some specimens the fourth quill is the longest,

the fifth almost as long; in others these relative lengths are transposed,

shewing, as pointed out by me some years ago in the 'Naturalist,'

that no distinctive character ought to be considered as certainly

established from the length of the quill feathers of the wing. The

first is very short, equal only to the tenth, the second to the seventh,

the third to the sixth. Greater wing coverts, pale red, barred with

dusky brown; primaries, brownish, tipped with dark grey, marked on

the inner webs with dusky bands, the inner margins of which are reddish

white: the bands are conspicuous on the under side; the tips are darker

than the rest; secondaries and tertiaries, marked as the primaries.

The tail, long and even, consists of twelve rather wide and rounded

bluish grey feathers, and has from three to six broad bands of blackish

brown: it is tipped with greyish white; under tail coverts, reddish

white, barred with rufous brown; the feathers on the legs barred with

the same. Legs, light yellow, thin, and long; toes, light yellow:

the latter are also long, the middle one being remarkably so, even

in comparison with the others: the third and fourth are connected

at the base by a web, which extends beyond the second joint of the

latter, and curves forward as far as that of the latter: the soles

of the feet are very protuberant; claws, black, pale bluish at the

base: they are very thin at the points; the inner and hind ones are

of equal length, and longer than the others.

Female; weight, about nine ounces; length, from about one foot two

to one foot four inches; bill and cere, as in the male; iris, bright

yellow; head and Crown, blackish grey; a white band passes from the

forehead over each eye, and runs into the white on the back of the

neck; neck and nape, brown, the shafts dark in front; chin and throat,

reddish white, with longitudinal lines of dark brown; throat and breast,

reddish white, transversely barred more or less clearly with dark

brown, each feather having five bars: in age the whole colouring approximates

to that of the male; back, rufous or greyish brown. The wings expand

to about the width of two feet four or two feet five inches; under

wing coverts, light red, barred with dusky brown; primaries, secondaries,

and tertiaries, greyish black, obscurely barred on the outer webs

with dark brown, and spotted with two or more large yellowish white

spots on the inner webs in the intervals, excepting towards the tips;

greater and lesser wing coverts, reddish white, broadly barred. The

tail, which is brown, has four darker bars of the same on the middle

feathers, and five on the side ones; their edge is better defined

on the lower than on the upper side; tip, whitish; under tail coverts,

white, with a few dark markings on the outer ones; legs and toes,

yellow; claws, black.

Some females, supposed to be very old, have much resembled the male

in colour.

The young are at first covered with white or greyish white down —even

in the nest the females are distinguishable by their superior size.

When fledged, the bill is dusky brown at the tip, and bluish at the

base: cere, greenish yellow; iris, light brown. Head and neck, reddish

brown, with some partly white feathers on the back of the latter;

the middle of each feather being dark greyish brown; breast, reddish

white, with large oblong spots of a dark brown colour: the middle

of each feather being of that colour, transversely barred with yellowish

red or light rust-colour—the bars becoming by degrees narrower

and brighter. Back, reddish brown; legs and toes, greenish yellow,

tinged with blue. Wings and tail, dark reddish brown, then bluish

grey, which becomes more pure as the bird advances in age; the tail

has three dark brown bands. The female is larger; she also has the

partly white feathers on the back of the head; the breast is whiter

than in the male, and the markings on it larger; the upper parts browner.

I have recently seen, in the admirably well-preserved collection of

Mr. Chaffey, of Doddington, Kent, a most remarkable variety of this

bird, a male, the whole plumage as white as snow.

"Such glance did Falcon never dart When stooping on his prey."

Marmion