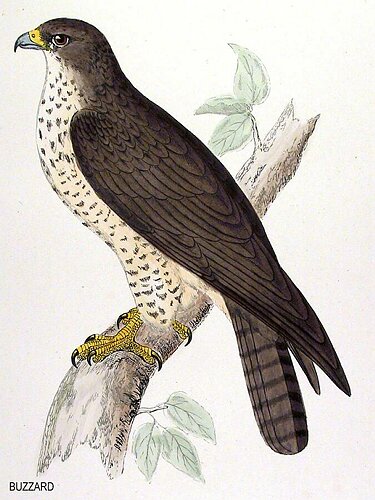

BUZZARD.

BOD TEIRCAILL, IN ANCIENT BRITISH.

Buteo vulgaris, FLEMING. Falco buteo, PENNANT. -Buteo—A kind

of Falcon or Hawk (Pliny). Vulgaris—Common.

DR. JOHNSON asigns as the meaning of the word Buzzard,

'a degenerate or mean species of Hawk,' but being by no means one

of the admirers of the author of the Dictionary in this behalf, I

shall take leave to differ as much from the present as from another

well-known definition of his touching the 'gentle art,' of which for

many years I have been a professor, while looking upon him, for all

that, in the words of Lord Macaulay, as 'a great and a good man.'

The Buzzard is plentifully distributed over nearly the whole of the

continent of Europe, and is also found in North America, and in the

more northern parts of Africa. It inhabits Spain and Italy, Denmark,

Sweden, Norway, and Russia, Holland and France, but does not appear

to be known in the Orkney or Shetland Islands. In England, Scot-land,

Wales, and Ireland, it is sufficiently abundant, affecting both the

wildest and the most cultivated districts, but in both taking a more

than ordinary care to choose such situations as will either exempt

it from the intrusion, or enable it to have timely notice of the approach

of an enemy. The Rev. George Jeans informs me of one formerly seen

for some time at Egham. Still, with all its precautions, and with

every aid that its own instinct and the most retired or the most rugged

localities can afford, it, like too many others of our native birds,

is gradually becoming more rare. The advancement of agriculture upon

grounds heretofore wild and uncultivated, the natural consequence

of an increase of population within a fixed circumference, and other

causes, contributing to this fact, which at all events a naturalist

must lament.

The Buzzard is found in a variety of situations, such as rocky cliffs,

chases, parks where timber abounds, or in 'ci devant' forests. It

remains in England throughout the year, but nevertheless, is partially

migratory: this in small companies, frequently, as hereafter stated,

in company with the Rough-legged Buzzard.

In Yorkshire it has been occasionally met with in most parts of the

county-frequently near Doncaster, Huddersfield, and Sheffield. In

Devonshire in various parts; and has also occurred at Falmouth and

Mylor, Cornwall; the latter in 1849, and was bought by - Bullmore,

Esq., for sixpence, Maelgwn and Penmaenmawr, Wales; one near Market

Weighton, September 18th., 1869, where they once bred; and in Scotland

near Dunbar, as, too, in Caithness, Invernesshire, East Lothian, etc.

It breeds at Pinhay Cliff, Devonshire, near Lyme Regis, Dorsetshire,

where I have often watched them, also near St. David's in Wales. A

pair have built at Kelly for several years at Mr. Reginald Kelly's,

he has written me word.

I am much indebted to my liberal-minded friend, Arthur Strickland,

Esq., of Bridlington-Quay, for the following striking notice of the

fact of its migration in this country, communicated to him in the

year 1847, by his brother, then residing at Coleford, in the Forest

of Dean, in Gloucestershire. I must observe that the letter was not

originally intended to be published.

' Coleford, 1847. 'I have a curious circumstance in Ornithology to

tell you. There is no account that I have heard of relating particularly

to the migration of some of the Hawks, proving them to assemble in

flocks for the purpose of migration, and going off together in large

parties like Swallows, but of this I have positive proof in the Common

Buzzard. On the 2nd. of August, 1847, just at sunset, we were assembled

in the yard to the number of five persons; we were busily engaged

talking on a fine bright evening: the air was filled as far as we

could see, (about forty yards to the north, and one hundred to the

south,) with great Hawks, all proceeding together steadily and slowly

to the westward. Those immediately above us were within gunshot of

the top of the house-with large shot I might have brought some down

from where I stood. The man called them Shreaks-a common name for

the Wood Buzzard. The evening was so bright, and they were so near,

that I saw them as plain as if they were in my hand. They were flying

in little parties of from two to five, all these little parties flying

so close together that their wings almost touched, whilst each little

party was separated from the next about fifteen or twenty yards: fourteen

parties passed immediately over us that I counted, but as I did not

begin to count them at first, and as I have no doubt the flock extended

beyond the boundary of our view, I cannot tell how many the flock

consisted of. On this day a remarkable change occurred in the weather,

which may have caused an early migration.'

Again, the same gentleman writing from Coleford in the following year,

1848, says-'Coleford, 1848. 'I last year wrote you a history of the

migration of large parties of the Great Wood Buzzard. This year, on

the 29th. of July, 1848, a party went over numbering forty, and the

next day another flight of eighteen. I calculate the Hawks in three

months must eat more than a ton weight of food, as I know that one

Hawk will readily eat more than four pounds weight of beef in a week-what

can they have lived upon? there is next to no game in the forest or

country anywhere.'

Whether the flights of the birds mentioned were adults moving from

one part of the country to another, or young birds leaving their paternal

home, in obedience to those laws of population to which even lordly

man is forced to submit, it is difficult, in the absence of ascer-tained

facts, to hazard a conjecture. Temminck has observed that the species

before us migrates at certain periods of the year, and that it is

at such times frequently associated with the Rough-legged Buzzard,

which, if so, is rather curious.

Their flight when thus migrating appears to be slowly performed- retarded

by various evolutions in the air-and many of the birds often remain

for days, and even weeks together, at some halting place or places

on their way.

In confinement the Buzzard is easily tamed, and becomes in fact quite

companionable. Various amusing anecdotes are recorded of different

individuals which have been thus kept. It has generally been described

as being of a slow and sluggish nature, but it is so only comparatively,

with reference to some other species of birds of prey, and must not

come under a wide and unexceptional censure. According to Bewick,

whom other writers seem to have followed in forming their estimate

of the character of the bird before us, it is so cowardly and inactive

that it will fly before a Sparrow Hawk, and when overtaken, will suffer

itself to be beaten, and even brought to the ground, without resistance.

I myself, however, as above suggested, incline much rather to the

opinion of Mr. Macgillivray, that the Buzzard is by no means such

a poltroon as he generally has had the character of being.

The Buzzard is described by some writers as flying low, but this is

by no means the result of repeated observations which I have had opportunities

of making upon it: I have almost invariably seen it flying at a very

considerable elevation. Unquestionably it does, because it must fly,

low, not only sometimes, but often; but that it passes no small portion

of its time in lofty aerial flight, I most unhesitatingly affirm.

The slow sailing of this bird, as I have thus seen it, is very striking-the

movement of its wings is hardly percep-tible, but onward it steadily

wends its way: you can scarcely take your eyes off it, but follow

it with a gaze as steady as its own flight, until 'by degrees, beautifully

less,' it leaves you glad to rest your eyesight, and if you look again

for it, you look in vain. When soaring aloft, the flight of the Buzzard

is even peculiarly dignified, if I may use such an expression, nor

do I know of any bird by which, on the wing, the attention is more

immediately arrested. It looms large also in the distance, and those

who have had frequent opportunities of comparing together its apparent

size and that of the Golden Eagle, have said that the former may easily

be mistaken for the latter, if both are not seen together in tolerable

propinquity.

Even when high in the air, particularly on a bright and sunny day,

the bars and mottled markings on the wings and tail, the motions of

which latter are also clearly discernible in steering its course,

appear visibly distinct.

The flight of this species appears heavy, but it is not so in reality:

a series of sweeps, when, in piscatorial language, the bird is on

the feed. It rises slowly at first, more after the manner of an Eagle

than a Falcon, and, when on the wing, proceeds sedately in quest of

its prey, which when it perceives, halting sometimes for a moment

above, it darts down upon, and generally with unfailing precision.

Its quarry is then either 'consumed on the premises/ or carried off

for the pur-pose to some more convenient or more secure place of retreat,

or to its nest, to supply the wants of its young. It does not continue

on the wing for a very long time together. When not engaged in flight,

it will remain, even for hours together, in the same spot-on the stump

of a tree, or the point of a cliff, motionless, as some have conjectured,

from repletion; and others from being on the look out for prey, at

which, when coming within its ken, to stoop in pursuit. It frequents

very much the same haunts, and may often be seen from day to day,

and at the same hour of the day, beating the same hunting ground.

I am inclined to think that the species of prey most naturally sought

by the Buzzard is the rabbit. It feeds, however, for necessity has

no law, on a great variety of other kinds of food. It destroys numberless

moles, of which it also seems particularly fond, as well as field

mice, of which Brehm has stated that when it has young it will destroy

one hundred in a day, and that thirty have been taken from the crop

of a single bird, leverets, rats, snakes, frogs, toads, the young

of game, and other birds, newts, worms, and insects. The latter, of

the ante-penultimate kind mentioned, it seems to have been thought

to have obtained, by some means or other from their pools, but such

a supposition is by no means necessary, for those little animals,

like many other water reptiles, are often to be found wan¬dering

on dry land-out of, and far away from their more proper element. The

way in which the Buzzard procures moles is, it is said, by watching

patiently by their haunts, until the moving of the earth caused by

their subterraneous burrowings, points out to him their exact locality,

and the knowledge of it thus acquired he immediately takes advantage

of to their destruction. The feet, legs, and bill being often found

covered with earth or mud is thus accounted for, and not by his ever

feeding on any such substance.

The Buzzard never, or very rarely, attempts to obtain its prey by

pursuit or to seize birds flying. It prowls about, and pounces down

on whatever may be so unlucky as to fall in its way. Feeding, as it

does, on various kinds of vermin, it is of great service in corn-growing

countries, and according to Mr. Meyer, is itself esteemed a delicacy

on the continent, notwithstanding the not over nice selection of its

own food. He also says that it will attack the Peregrine when the

latter has secured a quarry, and take it without opposition.

The yelping note of the Common Buzzard is wild and striking, its shrillness

conveying a melancholy idea, though as every feeling of melancholy

produced by any thing in nature must be, of a pleasing kind—when

heard in the retired situations in which this bird delights. One of

its local names is the Shreak, evidently derived from the sound of

its note.

They are very attentive to their young, and are said not to drive

them away so soon as other Hawks do theirs, but to allow them to remain

in company with them, and to render assistance to them for some time

after they had been able to fly, in the same way that Rooks and some

other birds do.

The Buzzard is extremely fond, even in captivity, of the task of incubation:

one at Uxbridge, a female, brought up safely several broods of chickens,

to which she proved a most kind and careful foster-mother. The landlord

of the inn, in whose garden she was kept, noticing her desire to build

and to sit, supplied her with materials for a nest, and with hen's

eggs for the purpose, and this was repeated with the like success

for several years. On one occasion, thinking to save her the trouble

of sitting, he provided her with chickens ready hatched, but these

she destroyed. She seemed uneasy when her adopted brood turned away

from the meat she put before them to the grain which was natural to

them. Several other similar instances are on record.

'Another instance' has been noticed near Lichfield: a female of the

same species, domesticated and kept in a garden, was set with some

eggs of the common poultry, which she hatched at the usual time. When

the chickens were freed from the shell, this strange stepmother defended

them in the most furious manner, scarcely allowing any person to approach

the wooden box in which they were hatched and kept, and to which they

retired whenever they chose; and no dog or cat could venture near,

without being stoutly assailed by the Buzzard. Its fury far surpassed

that of a common hen, but gradually slackened as they grew older;

the habits of affection, however, never entirely ceased, for the chickens,

after they became full-grown fowls, remained with it, and all lived

together in the same garden, in perfect harmony.'' -So writes Bishop

Stanley.

The Buzzard builds both in trees, and in clefts, fissures, or ledges

of mountains and cliffs, and if the latter are chosen, in the most

secure and difficult situations. One in particular I remember in a

most admirable recess, out of all possible reach except by being lowered

down to it by a rope. The nest is built of large and small sticks,

and is lined, though sparingly, with wool, moss, hair, or some other

soft substance. Not unfrequently, to save the trouble of building

a nest of its own, it will appropriate to itself, and repair sufficiently

for its purpose, an old and forsaken one of some other bird, such

as a Jackdaw, a Crow, or a Raven, and will also occasionally return

to its own of the preceding year.

Buzzards pair in the beginning of March, and may then be seen wheeling

about, and often at a great height above the place of their intended

abode, 'in measured time,' in slow and graceful flight.

The eggs are two, three, or four in number, generally the former,

and rather incline to a rotundity of form. They are of a dull greenish

or bluish white, streaked and blotted, more especially at the thicker

end, with yellowish or pale brown. Sometimes they are perfectly white.

Occasionally their markings are extremely elegant in the eye of a

connoisseur. I may here mention that I strongly suspect that many

colourings of different eggs are adventitious, and not intrinsic.

Mr. Hewitson, in his very much to be praised 'Coloured Illustrations

of the Eggs of British Birds, writes, 'Mr. R. R. Wingate had the eggs

of the Common Buzzard brought to him from the same place for several

successive years-no doubt the produce of the same bird. The first

year they were white, or nearly so; the second year marked with indistinct

yellowish brown, and increasing each year in the intensity of their

colouring, till the spots became of a rich dark brown.'

One variety is very pale yellowish brown, marbled over from the middle

to the end of the base with irregular blots and marks of darker shades

of the same.

A second is bluish white, handsomely marbled over with brown of two

shades, mostly near the smaller end and round the base, least towards

the middle.

A third is dull white, faintly speckled over from the centre to the

thicker end with minute light brown spots, and much marked at the

larger end with particles of brown.

A fourth is bluish white, with a very few specks and dots of pale

brown, and darker brown here and there. Some are perfectly white.

The Buzzard is one of those birds which either happily or un-happily,

as different naturalists may choose to consider it, varies very much

in plumage-scarcely any two individuals being alike. The feathers

also fade and wear much before moulting-the only permanent markings

are the bars on the tail. It is the upper part which varies most in

depth of tint, the general colour being brown, more or less deep or

dull. In the darker specimens a purple hue is apparent. The feathers

are darker in the centre, and lighter at the edges; the margins being

sometimes of a pale brown, or reddish yellow. Bewick says that some

specimens are entirely white, and others are recorded as nearly so.

The males appear to be lighter in colour than the females. Generally

they are, however, dark brown, though in some cases white prevails;

the feathers being spotted in the centre with brown. Weight, from

thirty to forty ounces; length, about one foot eight inches. The general

colour of the bill is black, or leaden grey, yellow at the edges,

and greyish blue where it joins the cere. The cere, which is bare

above and below, but bristled on the sides, is of a greenish yellow,

darker in specimens of darker colour; iris, yellowish brown, or pale

yellow, but it is found to vary in some degree, according to the general

tone of the colour of the bird, and sometimes approaches to orange.

The head, which is very wide and flattened on the top, is streaked

with darker and lighter shades of brown; occasionally with yellowish

white. Neck, short and wide in appearance-so much so, in connection

with the shape of the head and the general loose character of the

plumage, together with the habit of these birds of prowling for food

in the evening, to have led some to suppose than an approximation

is furnished by the Buzzards to the Owls.

The colour of the feathers of the neck is dusky grey, very much streaked

with brown; chin and throat, white, or nearly white. The breast, greyish

white, or yellowish white, also very much streaked with darker and

lighter shades of brown-some of the feathers being white, with brown

spots in the centre of each. In some specimens the breast is nearly

as dark as the back, in others it is belted beneath with a broad band

of a purple tint, and occasionally is entirely variegated with reddish

brown. The back, dark brown, sometimes shewing a purple hue. Wings,

large, measuring from four feet to four feet and a half in extent.

They are rounded at the ends, so much so that this feature is not

only clearly discernible, but a distinguishing mark of the bird when

on the wing: when closed, they reach nearly to the end of the tail.

The tips are deep brown, shaded at the base with pure white. The wings

beneath are lighter, being mottled with white and brown-they are crossed

irregularly with dark bars: greater and less wing coverts, dark brown;

primaries, brownish black; greater under wing coverts, and lesser

under wing coverts, dark brown. The tail, which has six, eight, ten,

or twelve narrow bars of alternate dark brown and pale greyish brown,

the last dark bar being the widest, is tolerably long, rather wide,

and slightly rounded at the end: the tips of the feathers are pale

reddish brown.

The under side of the tail is of a general greyish white, barred with

dark brown. The whole appearance of the bird is often extremely beautiful-the

upper surface being varied with a fine grey brown of different shades,

and reddish and yellow. Upper tail coverts, dark brown; lower tail

coverts, yellowish white, or white spotted with brown on each feather.

The legs, which are rather short, are feathered about a third down,

the bare part, which is yellow, being covered nearly all round, but

principally in front, with a series of scales. I do not give their

number for the reason mentioned in a previous instance.

The toes, bright yellow, and short-the third being the longest and

united to the fourth by a tolerably large web; the others are nearly

of equal length. In specimens of this bird of dark plumage, the colour

of the legs is correspondingly darker than in those of a lighter hue.

The toes are reticulated to about half their length; claws, black,

or nearly black, and though very sharp, not very strongly hooked.

The female is considerably larger than the male, measuring from one

foot nine to one foot ten inches in length, and nearly five feet across

the wings; sometimes as much as full five feet. The young birds while

in the nest are of a lighter colour than the old ones, and the tips

of the feathers are paler than the rest-the whole plumage being variegated

with brown and white, and the latter predominant on the back of the

neck. As they advance towards maturity, the plumage at each moult

becomes gradually of a darker hue, and at the same time the white

or yellowish white markings on the throat and lower parts become more

apparent and distinct. The iris is deep brown in the immature state,

and becomes of its permanent colour when the bird is adult.

'A beautiful variety,' says Mr. Meyer, 'of which there is a specimen

in the Zoological Museum, is also occasionally seen, but is comparatively

rare. The ground of the plumage in this variety is white, tinged in

various parts with yellow. The head is marked down the centre of the

feathers with narrow streaks of brown; a few of the feathers on the

breast are marked with arrow-shaped spots of the same colour, the

smaller coverts of the wings the same. The quill feathers are dark

brown towards the tips; the tail is crossed on a white ground with

dark brown bars, seven or eight in number, the bar nearest to the

white tip broader than the rest. In the white variety the eyes also

partake of the light colour of the plumage, and are pearl-coloured,

or greyish white; the cere and feet are also lighter in the same proportion,

being a pale lemon-yellow.'' One has been procured white all over

but for a few brown spots. The following account of this species from

Pennant, published in the year 1768, will show that ornithology has

made considerable advancement since his day, but that it has been

the reverse with the numbers of this, as with too many others, of

our British Birds.

'This bird is the commonest of the hawk kind we have in England. It

breeds in large woods, and usually builds on an old crow's nest, which

it enlarges and lines with wool, and other soft materials: it lays

two or three eggs, which are sometimes wholly white, sometimes spotted

with yellow. The cock Buzzard will hatch and bring up the young, if

the hen is killed. The young consort with the old ones some time after

they quit the nest, which is not usual with other birds of prey, who

always drive away their brood as soon as they can fly.

This species is very sluggish and inactive, and is much less in motion

than other hawks, remaining perched on the same bough for the greatest

part of the day, and is found at most times near the same place. It

feeds on birds, rabbits, moles, and mice; it will also eat frogs,

earth-worms, and insects. This bird is subject to some varieties in

its colours. We have seen some whose breast and belly were brown,

and only marked across the craw with a large white crescent: usually

the breast is of a yellowish white, spotted with oblong rust-coloured

spots, pointing downwards: the chin ferruginous: the back of the head

and neck, and the coverts of the wing, are of a deep brown, edged

with a pale rust-colour: the scapular feathers brown, but white towards

their roots: the middle of the back is covered only with a thick white

down: the ends of the quill feathers are dusky; their lower exterior

sides ash-coloured; their interior sides blotched with darker and

lighter shades of the same: the tail is barred with black and ash-colour:

the bar next the wing tip is barred with black and ash-colour: the

bar next the wing tip is black, and the broadest of all; the tip itself

of a dusky white. The irides are white, tinged with red. The weight

of this species is thirty-two ounces: the length twenty-two inches:

the breadth fifty-two.''

"Sometimes he'll hide in the cave of a rock, Then

whistle as shrill as the Buzzard cock."

WORDSWORTH.